The pursuit of well-being is different for adults than children, and so parents may be wracked with questions and uncertainty about how their child is actually doing. Growing up is hard enough without the undercurrent of change everyone is experiencing now.

The minds of youth process information differently – so age and personality and a host of other factors add to the complexity of diagnosing and treating mental health issues. Yet, candid conversations are vital because the prevalence of depression and anxiety are on the rise. And Tennessee is not an exception to that.

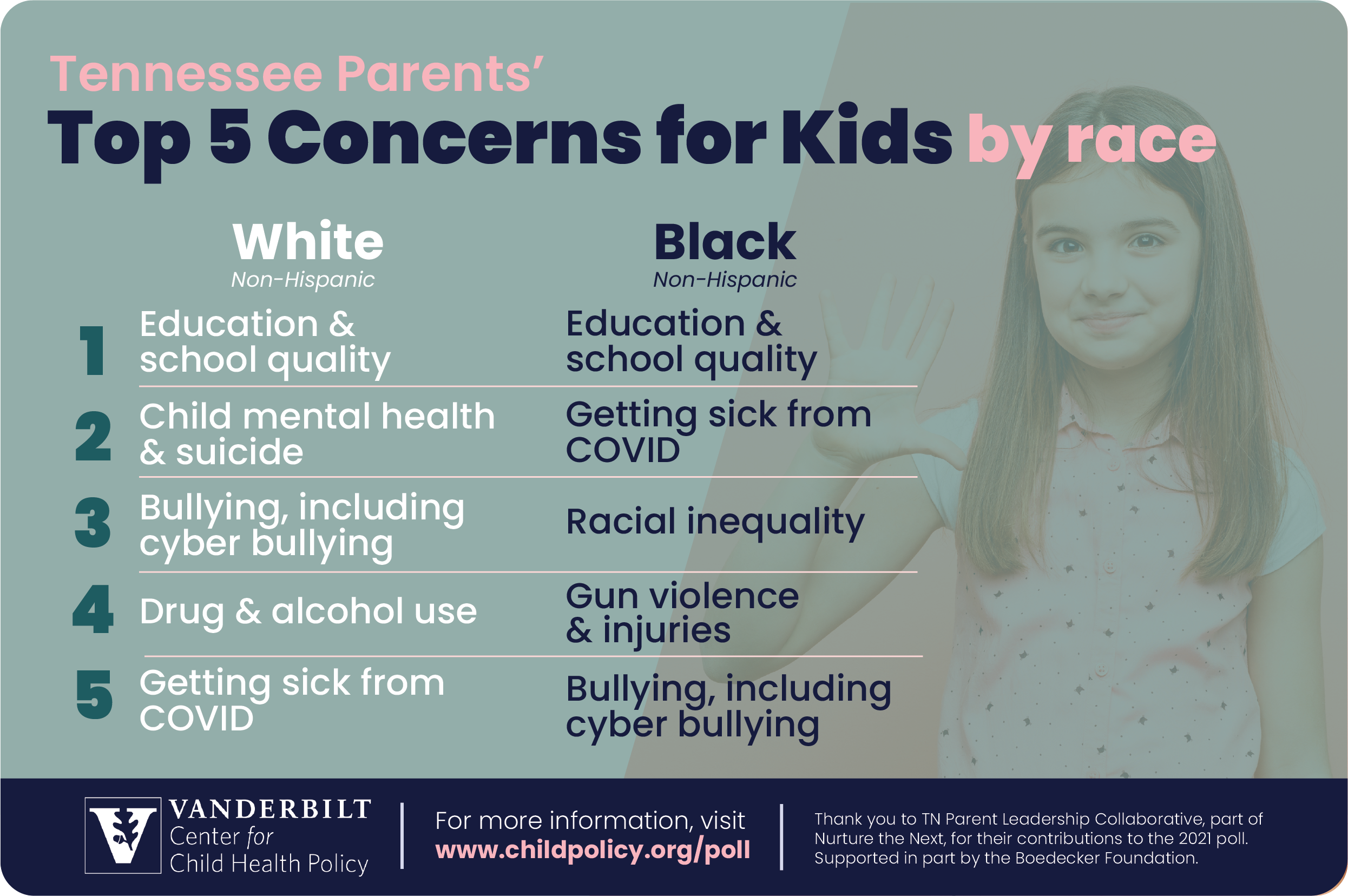

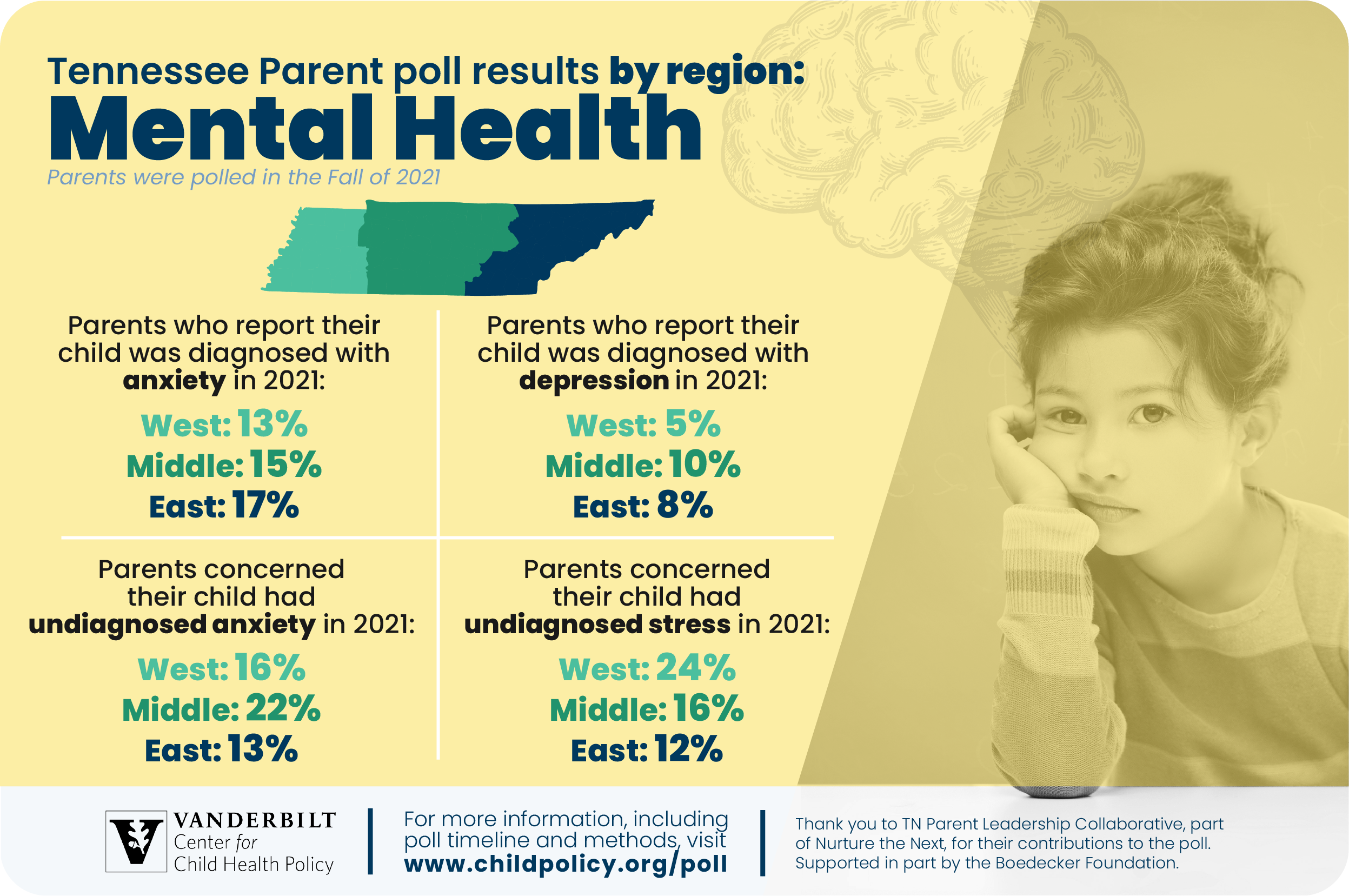

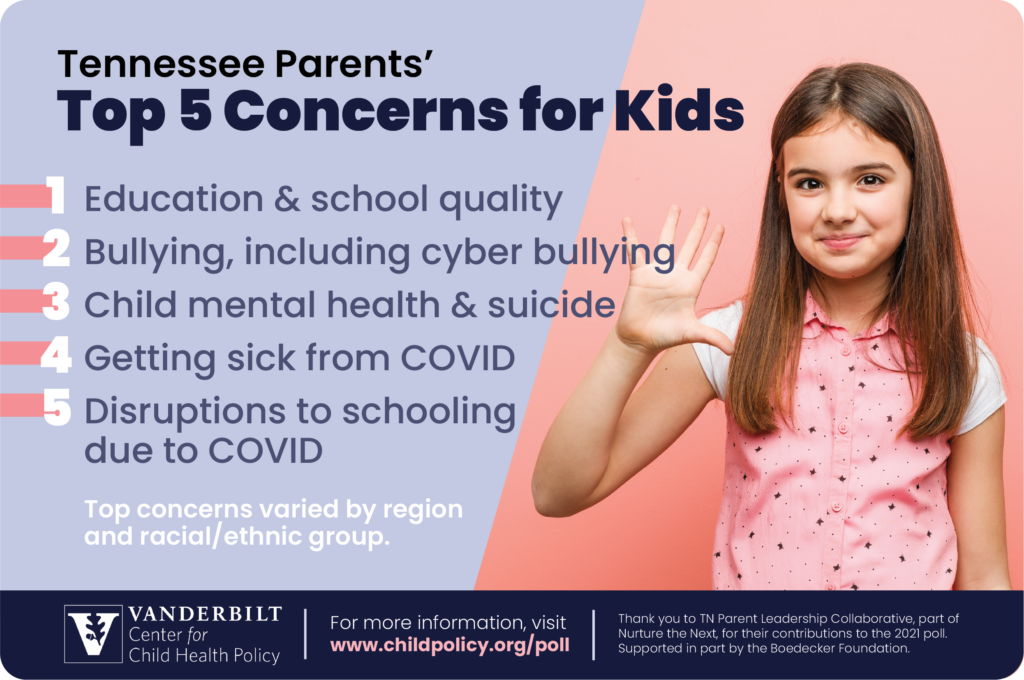

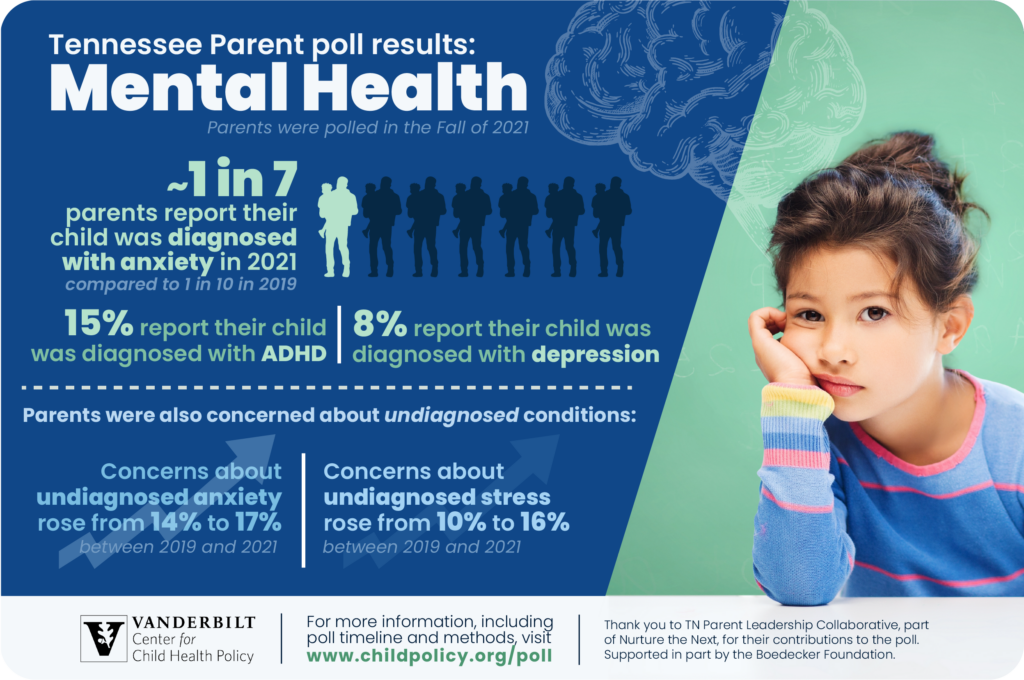

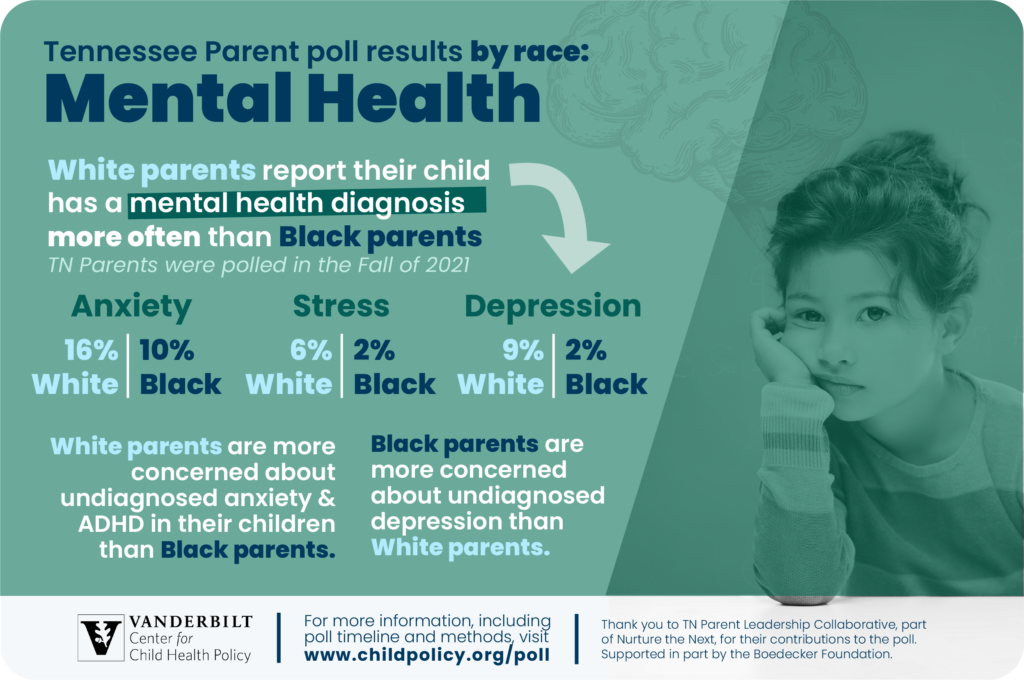

About 1 in 7 parents in Tennessee said their children were diagnosed with anxiety in 2021, an increase from 1 in 10 parents in 2019, according to the annual Vanderbilt Child Health Poll. Across the state, parents have more concerns about undiagnosed stress or depression than in previous years. Black parents are particularly concerned about undiagnosed depression.

The findings from researchers in the Vanderbilt Center for Child Health Policy underscore the pervasiveness of mental health diagnoses or concerns, an issue with complex roots and important ramifications for families now, and children as they age.

Three pediatric and adolescent psychiatrists talk about how children interpret life events; why having relationships with adults who are not parents is important; the gaps in access to care; and how improving mental health for youth requires upfront conversations and approaches that reflect real-world disparities. They also talk about what they want people to know about their jobs, and what they would change.

“The whole child and adolescent mental health world is so closely related to parenting and parenting seems to be in a crisis mode in this country. There just seems to be a lot more challenges that are ongoing — both culturally, politically. Hopefully there’s more attention paid to that objective: how do we help kids develop in a more resilient way, be more communicative around mental health and be able to identify things that can help wellness,” said Yasas Tanguturi, MD, MPH, Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and Associate Medical Director of Inpatient services at Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital.

Treating the mental health of youth is important for their immediate lives but also shapes their future as an adult. Appropriate and early intervention can, for instance, keep an anxiety disorder from spiraling into disruptions at school, at home and in friendships.

“The level of distress is the thing that keeps me up at night in the short term. You know, knowing that we have 15 kids in the emergency room waiting for acute care services; it’s knowing that the pediatricians are just completely burned out and feeling at their wit’s end because they don’t know what to do to help these kids and families. That’s the thing that causes me the most immediate distress,” said Meg Benningfield, MD, Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, and Director, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “But when we think about where we ought to invest our energy, it’s actually in the long term — the place where I get most excited about the potential to make an impact. The potential for hope is in the long term.”

“In terms of how it relates to pop culture a lot of it, for me, comes down to the language that we’re using to talk about mental health. If I could just wave a magic wand and change anything around being able to de-stigmatize mental illness, I would probably get rid of the colloquial terms, ‘psycho,’ ‘OCD,’ ‘bipolar’— all of those things that can make a subset of people that already have cards stacked against them, feel even more isolated and less willing to say, ‘Hey, I need help here,’” said Eboné Ingram, MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

Ingram wants people to not be afraid of psychiatrists or other mental health providers: “I don’t have a couch in my office. I’m not going to make you lie down and tell me about your dreams and stuff. I can’t even interpret my own dreams. And it’s not just about throwing medication at you and saying, ‘I’ll see you back in a month.’ It’s not really that at all.”

Mental Health Resources

- Child Outpatient Behavioral Health

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

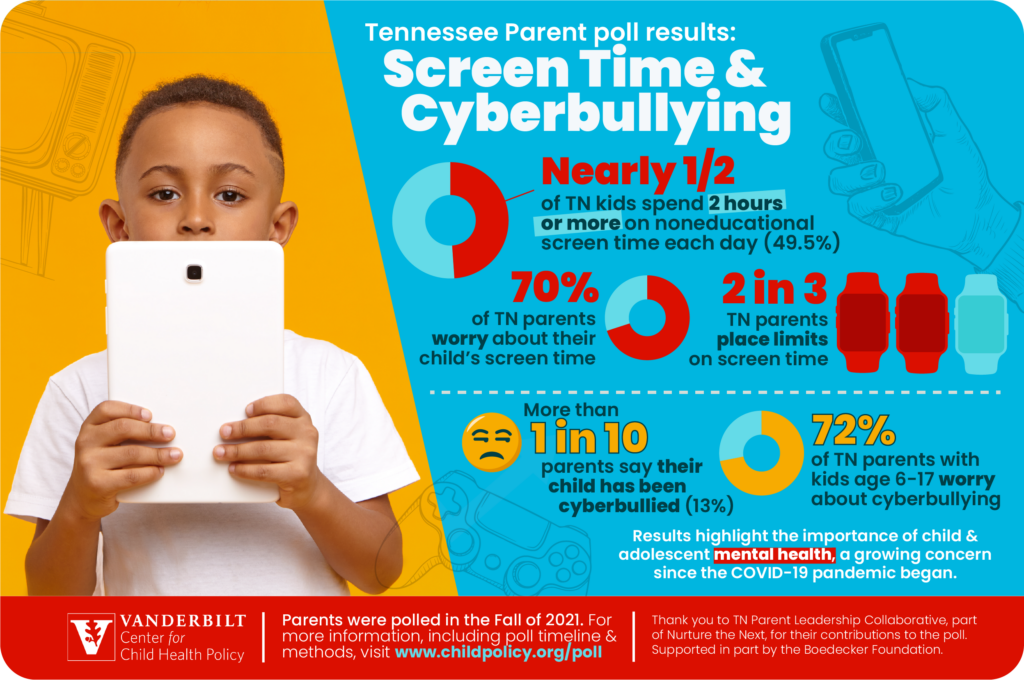

- Vanderbilt Poll: Mental health conversations are needed as children’s screen time increases

- How to talk to your teen about suicidal thoughts

- Parents of children who have experienced suicidal thoughts or behaviors needed

- Suicide prediction method combines AI and face-to-face screening

- More Teens with Tics Seen by Pediatricians

- Antidepressants for teens and children: what you need to know

- Study finds LGBQ people report higher rates of adverse childhood experiences than straight people, worse mental health as adults

- Feedback Loop Links Inflammation and Depression

- Going back to school can literally be a headache

- Brain Pathways Provide Insights into Antidepressant Function

- Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt creates new Vanderbilt Youth Sports Health Center

- Vanderbilt Child Health Poll: More parents report children diagnosed with anxiety in 2021 than previous years