For two decades, Vanderbilt University Medical Center researchers have been studying ICU patients on mechanical ventilation, examining ways to reduce delirium, coma, and their sequelae, which can include cognitive deficits, dementia, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety.

Vanderbilt’s Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center, established in 2018, developed the ICU Liberation Bundle, also known as the ABCDEF bundle, adopted by the Society for Critical Care Medicine for critical care that offers guidance for avoiding or responding to recognized or suspected delirium.

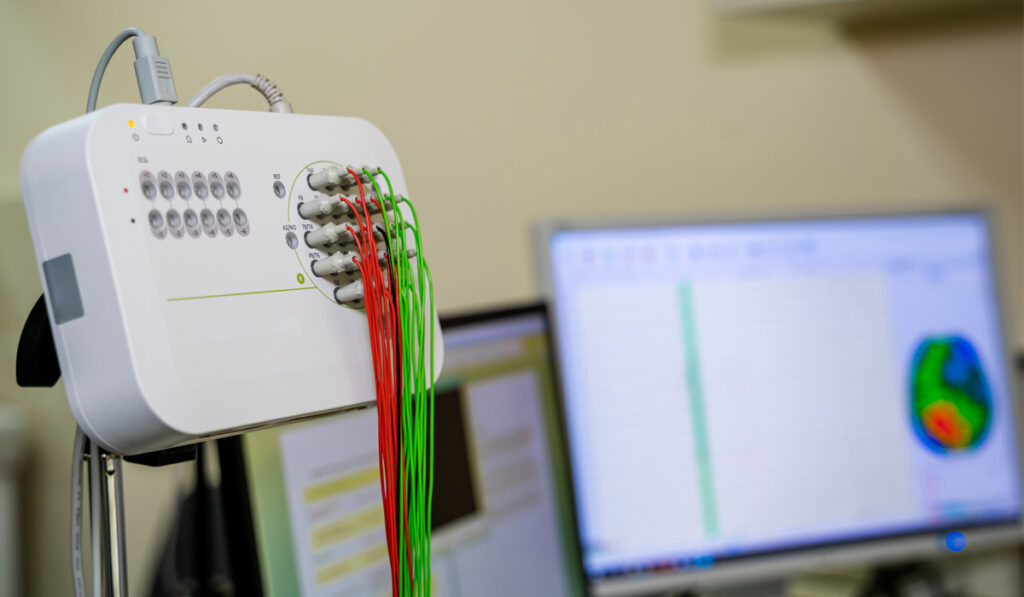

A new prospective cohort study emerging from the CIBS team interrogates the value of electroencephalogram (EEG) data in assessing delirium in mechanically ventilated patients, something particularly important for the large percentage of patients who do not actively display symptoms.

“Particularly for hypoactive delirium, it’s a way to see under the hood that we just don’t have right now,” said Shawniqua Williams Roberson, M.D., clinical director of ICU EEG at Vanderbilt and principal investigator on the study.

Williams Roberson’s work furthers the CIBS team’s goal of characterizing the long-term functions and patterns of cognitive dysfunction that can happen after ICU stays, predicting what those patterns are going to be, and identifying what predisposes people to long-term cognitive dysfunction. Continued analysis of EEG recordings may point toward a new normal in the ICU: continuous EEG monitoring with wireless data capture, enabling a new window into the cognitive state of patients.

Delirium and the EEG

Delirium is the disruption of consciousness marked predominantly by inattention and sometimes by vivid hallucinations and delusions. Common causes are sepsis, hypoxemia, metabolic problems such as liver and kidney disease, and sedatives given in the ICU. About 71 percent of patients experience delirium at some point during an ICU stay.

Williams Roberson explains that the EEG is the most promising tool for assessing delirium because it interrogates, on a moment-by-moment basis, activity inside the brain. She is capitalizing on computer modeling to build quantitative metrics that detect and make sense of the subtle changes the EEG picks up.

Delirium and Cognitive Deficits

In 2013, E. Wesley Ely, M.D., the Grant W. Liddle Professor of Medicine, and colleagues at Vanderbilt and the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System first demonstrated that delirium is the strongest ICU risk factor for long-term cognitive impairment. In a previous small study of ICU patients with EEG and formal post-ICU assessments, Ely, Williams Roberson, and colleagues found highly predictive associations between EEG values during their hospital stay and long-term cognitive performance.

In this recent study, Williams Roberson performed EEG testing on 25 mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU to assess correlations between EEG patterns and patients’ bedside clinical assessments.

This entailed twice daily delirium assessments using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale and the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU), a tool developed by Ely and his team. Roberson Williams sought to identify correlations between the results from these two instruments and 30 quantitative EEG values.

First, she identified four of these EEG values that were most independently contributive to identification of delirium and assessed whether predictions could be improved by adding these to an existing statistical model that uses clinical symptoms to predict delirium. She then combined the four features into one score to see if this would serve as a hypothetical “delirium indicator.”

The model that combined clinical tests with the EEG features generated a robust area under the curve, indicating that it was a better predictor of delirium than the clinical model alone.

She went further by examining 24-hour patterns of “brain health indicator” values, and found them to be consistently higher in the patients who never suffered delirium.

“This work indicates that our EEG data could be useful throughout the course of the 24-hour day – with all its potential cycles of wakefulness, somnolence, sleep, etcetera – in alerting the care team to when the patient is delirious or in coma,” Williams Roberson said.

Implications for ICU Care

One of the chief goals of the CIBS Center’s work is to be translational, so these and other findings are already leading to refinement of common ICU interventions, such as sedation holidays, spontaneous awakening trials, spontaneous breathing trials, stimulation from family visits, and mental health support following an ICU stay.

“We are making headway toward having the technology to perform these sensitive EEGs as a real-time biomarker of acute brain dysfunction,” Ely said. “Once we do, this kind of continuous measurement will add tremendous value to patient monitoring in a busy hospital ICU so that we can initiate treatments earlier to help patients survive and heal better.”