An infant’s nasal microbiome as it interacts with the immune system influences the child’s risk of becoming severely ill due to a respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, according to a recent study by Christian Rosas-Salazar, M.D., an assistant professor of pediatrics at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt. The study appeared in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

The study is the first to explore the influence of many different nasal microorganisms and how they interact with multiple immune factors during RSV infection in young children.

“A lot of researchers use one or two metrics to study one, two or maybe a few types of bacteria, but we used multiple metrics to examine the whole community of bacteria living in the nose,” Rosas-Salazar said.

Complex Interactions in Play

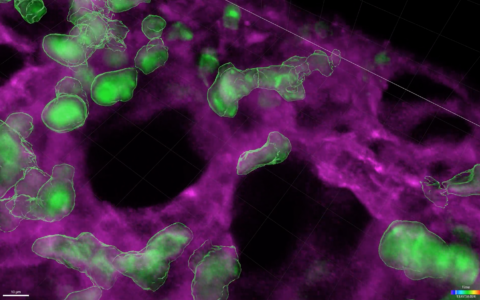

Just as human communities include various attributes such as population density, age distribution, household size and income, groups of microorganisms have diverse characteristics, as well.

“With microorganisms, you can make similar observations,” Rosas-Salazar said. “What’s the composition of the group? How many individual types of bacteria are there and how are they distributed?”

Members of the microbiome and various immune factors influence one another, and the nature of their interactions influences the mildness or severity of a child’s illness.

“Our major finding was that the respiratory microbiome determines RSV outcomes by working together with the immune response,” Rosas-Salazar said.

The microbiome and immune system factors such as cytokines not only act upon each other but also act together in associations that are complex and difficult to model, forming “many intricate relationships between the bacteria living in the airways and the infant immune response,” Rosas-Salazar said.

“You can have two immune mediators underlying the association, or three or four, and the more that are involved, the harder it becomes to interpret and understand.”

For the current study, the VUMC researchers teamed with a University of Wisconsin expert in microbiome factor analysis to examine the effects of 53 immune mediators.

“COVID has not only hit humans, it has also hit the microbiome.”

Microbiome Qualities Predict Outcomes

The researchers used data reflecting the experiences of 357 infants, aged 0 to 12 months, enrolled in the National Institutes of Health-backed INSPIRE study, a large (n=1,949) population-based cohort of healthy, term infants born between June 2012 and December 2013 in Tennessee. Only infants who had at least one acute RSV infection during their first RSV season, which has typically been wintertime, were included.

One metric, known as alpha-diversity, describes the richness of the taxa in the nose and was positively associated with a greater severity of illness, greater odds of the illness developing into an acute lower respiratory infection, and a higher number of wheezing episodes in the child’s fourth year.

In earlier work, Rosas-Salazar and his colleagues reported that infants with higher levels of Lactobacillus in their upper airway during an acute RSV infection were at lower risk for developing a recurrent wheeze.

“You can have two immune mediators underlying the association, or three or four, and the more that are involved, the harder it becomes to interpret and understand.”

COVID-19’s Surprising Effects

“Normally, many kids go to daycare and touch everything and then touch their noses, but they weren’t doing that during COVID,” Rosas-Salazar said. While staying at home, wearing face masks, and taking other precautions, they were exposed to fewer of the viruses a child typically encounters in daily living that serve as a big determinant of their personal microbiome. “COVID has not only hit humans, it has also hit the microbiome,” he said.

While RSV has previously been a winter virus, during the pandemic children have also developed RSV illnesses in summertime, Rosas-Salazar explained. “After COVID, we don’t know what RSV will do. Will it stay a winter virus?” The answers matter not only in pediatrics but for adults as well, since they too can develop serious cases of RSV.

“The worst thing you can do is try to kill the bad bacteria and actually kill the good ones.”

Possible Next Steps

Future studies will likely test interventions to alter the respiratory microbiome. For example, researchers can look for ways to boost commensal bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, or try to eradicate potentially harmful microorganisms, such as Moraxella, Haemophilus, or Streptococcus, Rosas-Salazar said.

“This type of microbiome intervention would have to be very specific, as the worst thing you can do is try to kill the bad bacteria and actually kill the good ones,” he said, adding that many RSV researchers are also working to develop an RSV vaccine.