Lealani Mae Acosta, M.D., an associate professor of neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, is site principal investigator on a trial for a new treatment that could help prevent frontotemporal dementia (FTD) in some people by influencing the amount of progranulin produced in the brain.

The work is part of the Vanderbilt FTD Clinic, one of about 20 such centers in North America and home to patient care services and a research program aimed at prevention and treatment of the disease on a number of fronts.

AL001, the drug being tested, is manufactured by Alector Therapeutics and targets an estimated 8-10 percent of FTD patients with a common gene mutation thought to cause their FTD. AL001 has demonstrated safety and efficacy through phase 2 and is now in phase 3 trials.

“This approach of looking at the forms of FTD where there’s a clear genetic cause, and targeting that one gene, gives us a higher chance of being helpful to at least this one group,” Acosta said. “We will continue to explore future gene targets.”

Pathology and Progression

Both Alzheimer’s and FTD are neurodegenerative diseases. Both involve the excessive build-up of proteins and affect motor function as they progress. The key distinguishing characteristic is that in Alzheimer’s, memory-related centers – the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex and later the cerebral cortex – are primarily affected, while in FTD, the executive function, seated in the frontal and temporal lobes, sustains the greatest impact.

“Since FTD affects behavior so strongly, patients may present with criminal, antisocial or inappropriate behavior – they can lose empathy or become apathetic,” says Ryan Darby, M.D., director of the Vanderbilt FTD Clinic. “Or they may act obsessive and compulsive, becoming addicted to sweet foods, for example.”

Darby says some people with FTD may have slowed motor movements similar to those seen in Parkinson’s disease, as well as bathing or self-care issues. Some may also develop amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, breathing issues or have difficulty swallowing and may require feeding tubes. A subgroup of these patients may develop language disorders, he added.

Clues on Etiology

FTD affects an estimated 50,000-60,000 Americans and is the second most common cause of dementia in people under the age of 65. About 60 percent of FTD cases occur in people between 45 and 64 years old.

In FTD, two proteins can accumulate to pathological levels: tau and TDP 43.

“We don’t know why they accumulate, but we do know that in some cases, there’s a clear genetic cause,” Acosta said.

Diagnostic progress is a step behind Alzheimer’s disease, Darby says, because there are no specific blood, spinal fluid or PET scans to identify FTD neuropathology.

“On MRI we see the damage that these proteins have caused, but we don’t yet have the blood and spinal fluid tests and the PET scan capabilities for early diagnosis of FTD,” he said. “Also, attempts at diagnosis may be stopped prematurely because the symptoms aren’t what people are looking for when they think about dementia. The patients we see may have pretty normal memory testing.”

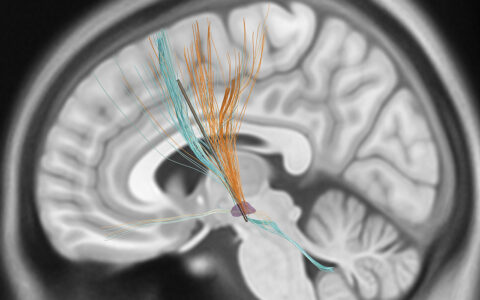

Darby’s seminal research on functional brain networks and atrophy network mapping has been pivotal in describing FTD and paving the way for understanding origins and associations within the brain, guiding research on this and other brain disorders.

State of the Research

Of the handful of gene mutations that have been identified as potential culprits, the gene controlling progranulin production holds particular interest. Many patients with FTD cases have a granular mutation associated with an underproduction of progranulin, which is expressed in both the central nervous system and peripheral tissues.

AL001, a recombinant human anti-human sortilin monoclonal IgG1 antibody, offers a potential means of preventing or slowing the disease in this population. An intravenous drug, AL001 is given monthly to block progranulin degradation in the body. Doing so causes endogenous levels to rise naturally.

“In small phase 2 cohorts, we have seen not only a reduction in biomarkers, but about a 48 percent reduction in clinical decline over one year, which is very promising,” Acosta said, adding that additional FTD research is also underway beyond the phase 3 trial.

“We are part of a research consortium with other centers in the United States and Canada, where we’re recruiting patients for yearly visits to get really comprehensive blood tests, spinal fluid, brain imaging and neuropsychological testing, to try and understand the disease, how it starts, and how it progresses. This includes patients, but also family members who might be genetic carriers.”

Darby adds that other research avenues are near inception. One includes introducing adeno-associated virus vectors into the cerebral spinal fluid to try to directly modulate the gene.

Symptom Treatment and Care

“For now, the available drugs and therapies for FTD are mostly psychiatric medicines that target the symptoms like apathy or disinhibition,” Darby said. “The same medicines used for obsessive compulsive disorder, for example, can be effective at quelling compulsive behaviors in FTD.”

The FTD Clinic at Vanderbilt helps patients on many fronts beyond diagnosis and medication therapy.

“There are speech therapists for language issues, and occupational and physical therapists for motor issues as well as psychologists and social workers,” Darby said. “We also have a close collaboration with a caregiver support group in Nashville that is a powerful organization in helping connect families locally and across the country.”