Rates of hepatitis C have been steadily increasing over the last several years, in large part due to the opioid crisis.

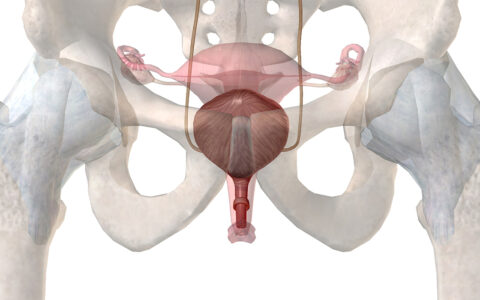

More than 65 percent of hepatitis C patients fall between the ages of 20 to 39, according to 2018 data. Because this age range overlaps with common childbearing years, perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus is also increasing.

To address these alarming trends, investigators at Vanderbilt University Medical Center have recently launched a perinatal hepatitis C clinic to implement CDC-recommended universal screening of pregnant patients at Vanderbilt and outlying clinics, while establishing the patient’s connection to care.

This effort, combined with new research on hepatitis C infections in pregnant patients and newborns at the Vanderbilt Center for Child Health Policy, is placing more focus on the care of parents and babies whose health is being impacted by the opioid crisis.

Springboard to Health

Launched with funding from Gilead Sciences, , the new perinatal hepatitis C clinic is a collaborative program between the Divisions of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Infectious Diseases, and the Department of Pediatrics. A major goal of the clinic is to expedite postpartum treatment by connecting pregnant patients diagnosed with hepatitis C and their infants to continued postpartum care.

“While we do not have medication that can treat hepatitis C during pregnancy, we can treat hepatitis C after delivery and in the postpartum period,” said Soha S. Patel, M.D., director of the new clinic and an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine at Vanderbilt.

“This clinic will provide resources to women diagnosed with hepatitis C and link them and their babies to specialized care and treatment postpartum.”

Unfortunately, Patel explains that many women do not know that treatment is available. She reports that as many as 40 percent of patients do not attend their postpartum follow-up visits, according to data from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“Currently, if a patient is diagnosed with hepatitis C, they would be referred to gastroenterology or infectious disease during the pregnancy and then, hopefully, receive treatment in the postpartum period – if they are able to follow up,” Patel said.

Founders of the new clinic hope to connect patients to specialists earlier in their pregnancies.

“This clinic will provide resources to women diagnosed with hepatitis C and link them and their babies to specialized care and treatment postpartum,” she said.

Trends at the Community Level

To better understand the individual and community factors associated with hepatitis C infections during pregnancy, researchers at Vanderbilt not involved in the clinic, including Stephen Patrick, M.D., director of the Center for Child Health Policy, recently completed a study in collaboration with the RAND Corporation analyzing a total of 39,380,122 live births across all U.S. counties.

The team’s findings, reported in JAMA Health Forum, show that a rural address, higher rates of employment, and greater access to obstetricians were associated with a lower risk of hepatitis C infection during pregnancy.

“Our findings are an important reminder that characteristics of the communities where people live can influence outcomes for pregnant people and babies,” Patrick said.

The researchers also noted that people at highest risk for hepatitis C infection during pregnancy were American Indian/Alaskan Native and white individuals without a college education.

While there tends to be a higher prevalence of opioid use disorder and hepatitis C among pregnant individuals who are white, health disparities still play a significant role in diagnosis and treatment for Black adults and their babies.

“Our findings are an important reminder that characteristics of the communities where people live can influence outcomes for pregnant people and babies.”

“Black people are less likely to receive evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder, Black infants are less likely to be tested than white infants for hepatitis C, and Black parents whose infants are placed in foster care for substance exposure are less likely to be reunified with their parents,” said Patrick. He noted that similar disparities are believed to exist for members of the American Indian/Alaskan Native population, but studies of minority groups are incomplete.

Developing Equity

“As systems are developed to address the rising numbers of mothers and babies affected by hepatitis C, it is critical that interventions are applied equitably to address unequal treatment in these systems of care,” Patrick said.

Hepatitis C rates will likely continue to increase as long as rates of opioid use disorder are rising, Patrick stressed.

“We still have a long way to go to get control of the opioid crisis as a whole but, as clinicians and policymakers, we can take steps to mitigate potential harm now.”