While nearly all Americans have arterial plaque buildup quite early in life, not everyone winds up having a heart attack or a stroke. Researchers searching for the reasons that some people do while others don’t have identified platelets as key contributors to the formation of errant clots, by studying the problem in patients with upper respiratory infections, such as the flu and COVID-19.

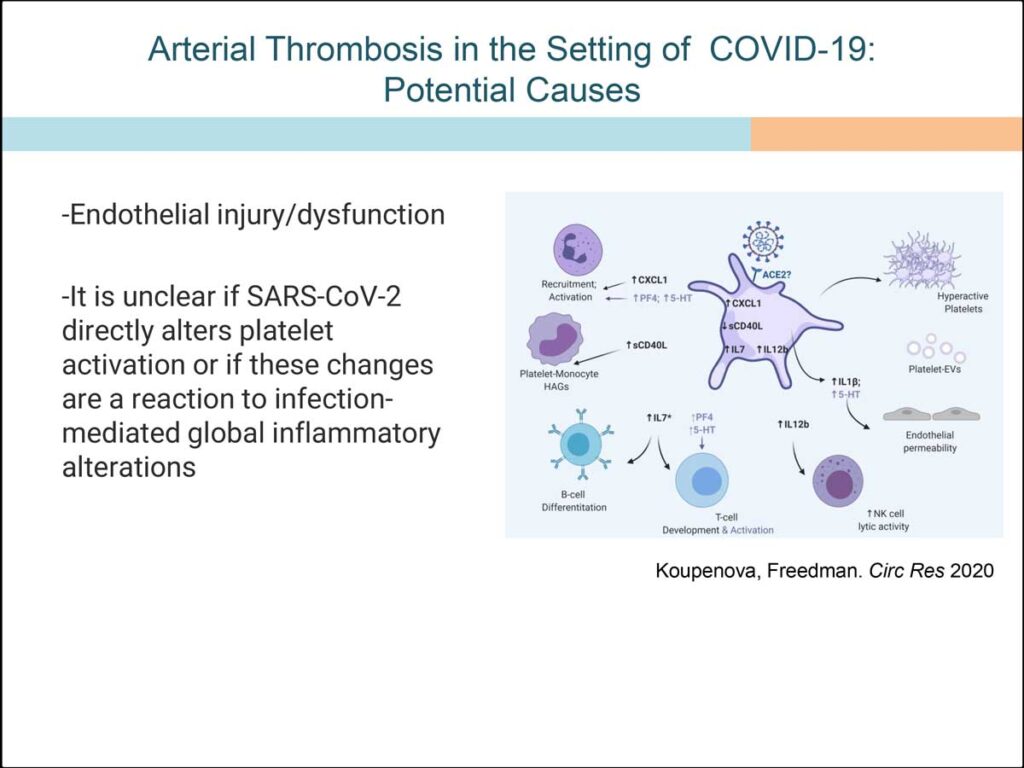

“People with the flu face a much higher risk for a dangerous clot in the week or two after infection, and the risks are heightened to an even greater extent among COVID-19 patients,” said Jane E. Freedman, M.D., the Gladys Parkinson Stahlman Professor of Cardiovascular Research and director of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Identifying a root cause

Decades ago, Freedman said, she and her colleagues realized that they needed to look beyond classic cardiovascular risk factors like family history, obesity, or lipids, which are associated with atherosclerosis.

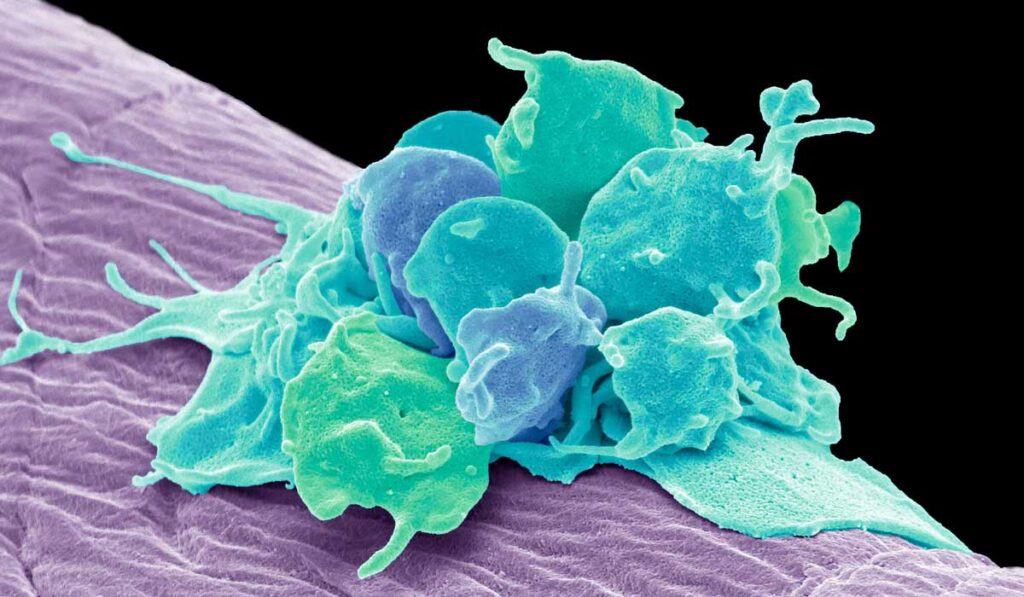

“Traditional risk factors all can lead to a narrowing of the arteries, but almost all of us have some degree of narrowed arteries,” she said. “They set the stage, but they are not typically the trigger that causes a clot. It turns out that platelets cause the clot.”

Freedman said she began considering the potential in platelets at a time when few scientists viewed them as factors in immunity.

“People with the flu face a much higher risk for a dangerous clot in the week or two after infection.”

“Years ago, my colleagues and I started to observe interesting immunity genes in platelets, especially in people who had had heart attacks,” she said. “People always think of platelets as just being there to prevent bleeding and never thought about them doing anything else.”

However, studies started to appear showing that contracting the flu or pneumonia put people at heightened risk of heart attack for one to two weeks after infection. In addition, researchers found that vaccination against those illnesses reduced the associated heart attack risk.

Platelet immunity – a double-edged sword

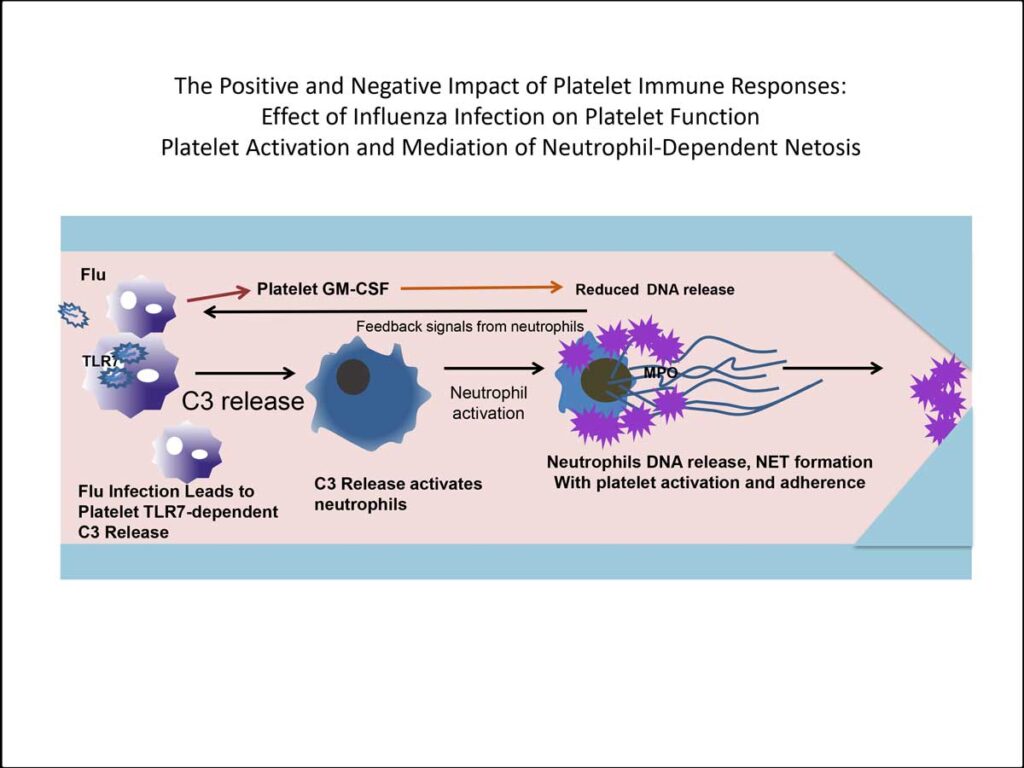

Freedman’s research showed that many flu patients also have influenza virus or viral particles in their platelets.

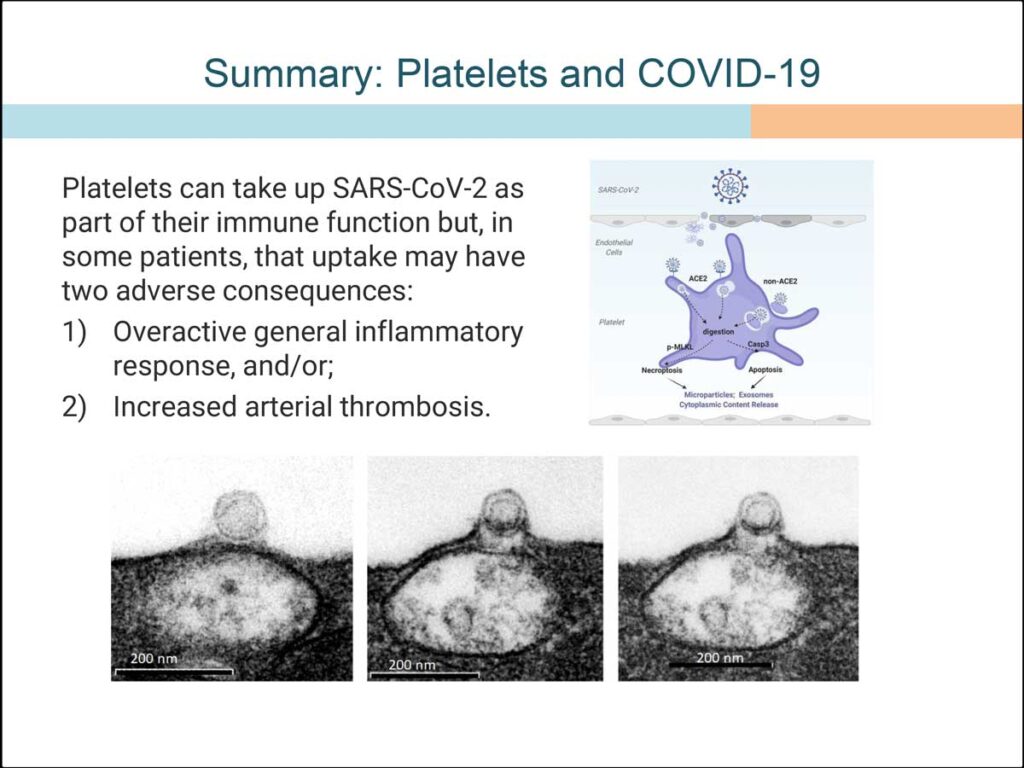

“Platelets were interacting with the flu, and we now know they interact with COVID, signaling white cells to turn on to help fight off the infection,” Freedman said. “The downside is that the platelets sometimes turn things on too much, overstimulating the white cells.”

Over-activated white cells release a substance called NETs[1] from their DNA, Freedman explained. “It’s a sticky process and can lead to the platelets becoming activated, which causes clots.”

“These findings testify to the importance of people getting their vaccines to prevent these respiratory infections.”

Freedman’s team directly observed NETs in action in mice and viewed evidence of the same process in blood drawn from patients with the flu.

Clinical implications

“If COVID gets into your bloodstream, it’s looking like platelets are one of the body’s first lines of defense,” she said. “They do eventually signal the white blood cells, too, but they look like the first immune-system actors to start getting rid of the virus.”

Platelets’ ability to thwart the SARS-CoV-2 virus may be especially important for individuals at high risk for cardiovascular events stemming from respiratory infections.

“These findings testify to the importance of people getting their vaccines to prevent these respiratory infections,” she said. The findings also show need for patients who routinely take an anticoagulant to be extra vigilant about it after contracting an upper-respiratory infection.

[1] NETs stands for “neutrophil extracellular traps.” A NET is a sticky mesh made up of extracellular DNA and nuclear and granular proteins that captures and kills pathogens.