Proximal amputation of a limb can cause abrupt changes to the body’s size, compartments and physiologic responses. Research has shown that in cases with preoperative comorbidities, medications used in treating heart, lung and other organ systems may warrant redosing.

A study published in the American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation by researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center – the first of its kind – finds that while most cases of high-level limb loss involve preoperative polypharmacy, the number of medications, dosing levels and potential drug-drug interactions remains the same or increases.

“Major limb loss results in both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic postoperative changes that impact medication dosing,” said Gerasimos Bastas, M.D., director of the Vanderbilt limb loss rehabilitation program and lead author on the study. “Yet often, these changes aren’t taken into consideration at discharge. It’s a very tricky landscape; we’re trying to call attention to it.”

Analyzing Dosing Trends

To gauge the scope of the problem, Bastas and colleagues performed a 3-year retrospective chart review of 216 cases of high-level limb amputation. Using the Synthetic Derivative, Vanderbilt’s database of deidentified medical records, they scrutinized pre- and postoperative medications, dosing changes and drug-drug interaction warnings. Postoperative profiles factored in home medication reconciliations.

The researchers found that the number of medications increased in 76.9 percent of cases, remained the same in 10.6 percent and decreased in 12.5 percent. The average number of medications was seven preoperative and 10 postoperative. In the 87.5 percent of cases where medications were present both pre- and postoperative, dosing remained the same or increased for the majority of agents (83.5 percent).

Drug-drug interaction warnings also increased, which Bastas says may be attributable to postoperative analgesics interacting with prior psychoactive medications.

Key Considerations

In major limb loss, a patient can lose 15-18 percent of their body mass, Bastas said. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations of this loss are nuanced, he noted, and many providers often aren’t aware of just how significant they can be.

“Major limb loss results in both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic postoperative changes that impact medication dosing, yet often, these changes aren’t taken into consideration at discharge.”

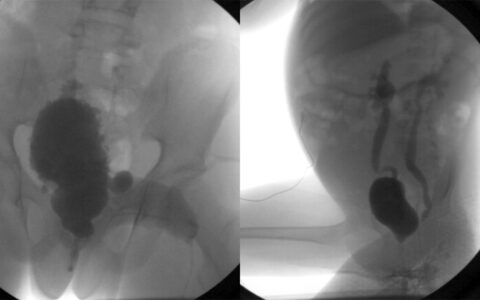

Limb loss has particular impact on cardiorespiratory systems. “For example, when a patient suffers a lower limb loss, they may become tachycardic, prompting their physician to overprescribe beta blockers,” Bastas explained. “Similarly, when a proximal upper limb loss amputation is performed, it affects breathing function; people can lose one-fifth to one-fourth of their lung capacity.”

Kidney function-based medication dosing can also be affected after major amputation surgery. “The typical estimations based on serum creatinine levels become skewed,” Bastas said, “because the patient has lost muscle-containing compartments and the relative concentration of the creatinine has decreased.”

Using AI to Effect Change

Pediatric medicine now has established dosing guidelines, and in geriatric medicine “start low, go slow, deprescribe” is the operating practice. There are dosing guidelines for bariatric surgery and maternal fetal medicine – both of which cause significant mass loss from the body. Yet, there are currently no practice guidelines for perioperative limb loss care. Bastas hopes that through more research, practice guidelines can be established that help improve long-term outcomes.

“This is a big challenge we have in medicine collectively. Explaining it to people mechanistically – it has a lot of ramifications.”

One simple answer could be, he says, that when a patient has an extended hospital stay an algorithm would trigger a prompt in their medical record to reevaluate dosing. “It’s a training and heuristics problem. We quite possibly need aids to guide us in our decision making.”

Bringing People “Into the Know”

Bastas is on a mission to educate both patients and providers regarding the postoperative changes resulting from limb loss. At Vanderbilt’s limb restoration care clinic, educational support is a key element, he said. “When a patient comes in for preoperative consultation, we educate them on the implications of their medications, and they take that information back to their other providers.”

Physiatrists at the clinic work closely with multiple specialists – orthopaedic surgeons specializing in upper and lower limb loss, physical and occupational therapists, clinical pharmacists and plastic surgeons. “We reach out to our colleagues to make sure they’re informing patients about the implications of this intervention,” Bastas said.

Bastas has led Vanderbilt Grand Rounds for colleagues in physical medicine and rehabilitation, cardiology, vascular surgery and anesthesiology highlighting considerations of limb loss. He also speaks to providers at other institutions and state societies for orthotics and prosthetics. “This is a big challenge we have in medicine collectively,” he said. “Explaining it to people mechanistically – it has a lot of ramifications.”