A large retrospective study by Vanderbilt University Medical Center researchers represents a major step toward understanding functional psychogenic non-epileptic seizure disorder and its associations. Evidence from deidentified patient data affirmed a high association of functional seizures with psychiatric conditions, and unveiled new ties with cerebrovascular disease. The findings were recently published in JAMA Neurology.

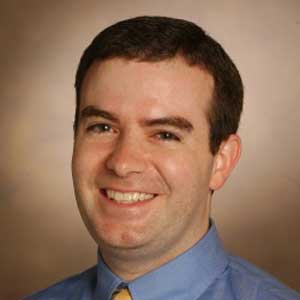

This study was clinically guided by Kevin Haas, M.D., clinical director of the epilepsy surgery program and EEG laboratory, and led by primary investigator Lea Karatheodoris Davis, Ph.D., an associate professor of genetic medicine, psychiatry and biomedical informatics. First author was Slavina Goleva, a doctoral student in molecular physiology and biophysics.

“One of the big problems is that functional seizures are misdiagnosed as epilepsy. As a result, people are treated with epilepsy drugs for years, or just not diagnosed,” Haas said. “Hopefully, this research will encourage early evaluation at an epilepsy center where a definitive diagnosis can be established – sooner rather than later.”

Epilepsy’s Doppelgänger

Functional seizures present with signs and symptoms similar to epileptic seizures, but often manifest with longer duration events, a fluctuating course and asynchronous movements.

The median years to diagnosis of functional epilepsy is 6.6, according to the new study, reflecting how difficult diagnosis is based on symptomology alone. “There’s a subset of patients where even a trained specialist wouldn’t be able to distinguish between a functional seizure and epileptic seizure if it happened right in front of them,” Haas said. Epilepsy drugs are not only ineffective for functional seizures, but may have serious side effects, he added.

Only EEG monitoring during seizure activity can inform a diagnosis. “Functional seizures are not associated with ictal electroencephalographic discharges, the trademark signs of epilepsy,” Haas explained. “Most patients need continuous video EEG monitoring for 3 to 5 days with anti-seizure medication withdrawal to accurately determine whether they are having epileptic seizures, functional seizures, or both.”

“There’s a subset of patients where even a trained specialist wouldn’t be able to distinguish between a functional seizure and epileptic seizure if it happened right in front of them.”

Probing Associations

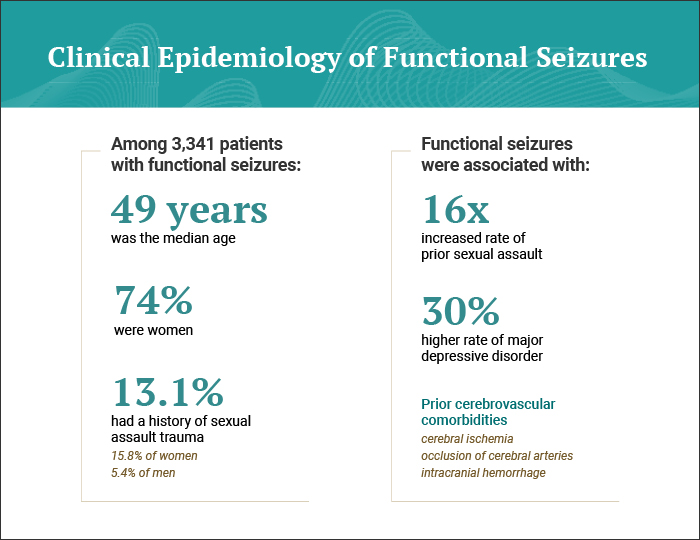

The study included EHR data from over 500,000 Vanderbilt patients, including adults with functional seizures, epilepsy, functional seizures and epilepsy, and a control population. The researchers developed clinically validated algorithms to investigate comorbidities and other factors associated with functional seizures.

Results confirmed significantly more women than men had functional seizure disorder. The study also found strong associations between functional seizures and PTSD, anxiety and depression. Sexual assault trauma was found in the histories of 13.1 percent of patients with functional seizures, compared to only 2.8 percent of patients with epilepsy.

“Our study replicated some key findings that trauma can be a contributing factor in the development of functional seizures. This doesn’t mean that everyone with functional seizures has experienced trauma or the converse. But it does give us some insight into the neurological consequences of trauma,” Davis said.

Researchers also found novel associations with cerebrovascular events. Functional seizures were associated with greater risk of experiencing transient cerebral ischemia, occlusion of cerebral arteries or intracranial hemorrhage.

Said Haas, “It may be that brain trauma or even psychological distress from the cerebrovascular disease is causing these functional seizures. This parallels data demonstrating that stroke is a risk factor for later-onset epilepsy. Alternatively, patients with functional seizures may have a higher risk of having other functional neurological disorders, including stroke-like symptoms.”

“This study is the first to give some hard numbers to a large population on the incidence and prevalence.”

Enhancing Mental Health Support

While Haas says only cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to directly reduce functional seizures, treating underlying PTSD, depression or anxiety is also critical for affected patients. “Addressing co-existing mental health issues should improve quality of life for people with functional seizures,” he said.

Haas says epileptologists are trying to take a more active role in the care of patients with functional seizures. “Here at Vanderbilt, we are on track to establishing a multidisciplinary clinic between neurology and psychiatry, to provide follow-up and better therapy options for these patients.”

As it stands today, Haas says that patients suffer not only long diagnostic delays, but a high rate of comorbidities and significant stigma due to limited knowledge about functional seizures. “This study is the first to give some hard numbers to a large population on the incidence and prevalence,” he said. “This understanding should help focus future research on identifying additional treatments for people with functional seizures.”