The rapid elevation of patients critically ill from COVID-19 offers unique learning opportunities for the medical community. Studying the sequelae of intubation is a prime case in point. Through an NIH grant, an otolaryngologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center is working with colleagues at Columbia University and University of Wisconsin on a study of COVID-19 post-intubation outcomes. Their findings may broadly influence intubation practices.

“We have known for some time that long duration endotracheal intubation can impact laryngeal function, leading to impaired breathing and communication even after hospital discharge,” said Alexander Gelbard, M.D., associate professor of otolaryngology at Vanderbilt and co-director of the Complex Airway Reconstruction program (AeroVU) at Vanderbilt. “Now, when people with COVID-19 require 14 to 21 days of intubation, we are seeing this problem magnified on a larger scale. Impaired laryngeal function can have a major effect on what their life is like after they recover from critical illness and leave the ICU.”

The researchers will examine the impact of preemptive strategies – a smaller tracheal tube, a switch to tracheostomy, an examination prior to discharge, and ongoing check-ups – as well as corrective treatment of ulceration and other laryngeal damage.

Intubation Problems Magnified

“In addition to creating new problems, the pandemic has also magnified problems that predated COVID-19,” Gelbard said. “As the number of patients affected with COVID-19 has increased, people are presenting three months after discharge, complaining that they can’t breathe. When we examine them, we see that they aren’t moving air well because severe scar tissue is limiting movement of their vocal cords.”

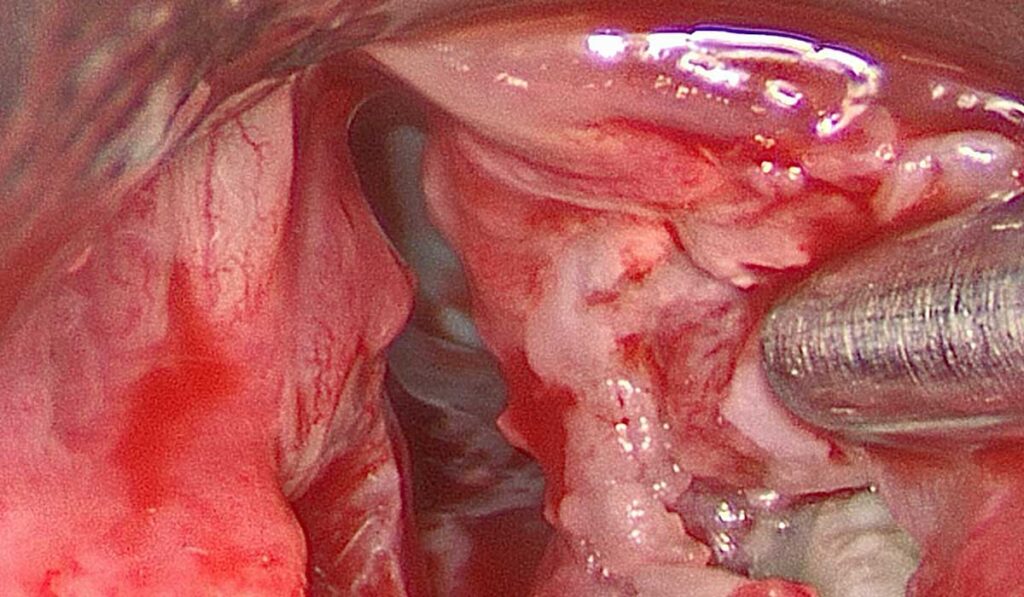

In a previous study, Gelbard and colleagues found acute laryngeal injury in 57 percent of patients intubated for 12 or more hours. If mucosal ulcerations develop, treatment typically entails debriding devitalized tissue and treating local inflammation. His research group has shown that early treatment appears to prevent the most severe complications after intubation.

Severe cases require healthy tissue grafts, Gelbard says. “The exposed cartilage doesn’t possess an effective mucosal barrier. Bacterial seeding can result, eliciting a robust immune response and triggering inflammation and subsequent fibrosis.”

“People are presenting three months after discharge, complaining that they can’t breathe.”

Early treatment may prevent severe fibrotic contractures from forming. Once the scar tissue and fibrosis have set in, Gelbard says solutions become far from perfect. These include endoscopic dilation and sometimes reconstructive surgery, which may enable a partial recovery of function. The new study seeks to identify early treatment points that could prevent life-altering consequences of intubation, like unilateral vocal cord injury.

Primary Prevention a Priority

Gelbard’s team plans a longitudinal study of 300 to 500 patients, post discharge, evaluating these early decision points in primary prevention:

- The impact of downsizing tracheal tubes, a choice that is weighed against the primacy of adequately clearing obstructive pulmonary secretions.

- Decisions to switch to tracheostomy, which reduces laryngeal injury risk, but heightens the viral exposure risk for providers.

- Pre-discharge examination of the airway if acute laryngeal injury is suspected. This may yield a high return, both in objective laryngeal function and in subjective patient-reported quality of life.

Once the patient is home, the study team will use a smartphone app to track their symptoms, focusing on communication, breathing, and overall quality of life. These self-reports will be coupled with physician-based evaluations of their laryngeal function.

Broad Dialogues, Broad Dissemination

Gelbard says the research goal is to learn what treatments work best for these patients. “Then we want to be able to communicate this to the range of surgeons we have who take care of those problems,” he said.

This work is an outgrowth of what Gelbard describes as a COVID-19-accelerated collaboration between specialists in critical care, critical care anesthesia, otolaryngology, trauma, and even general surgery. “Bringing these issues to the forefront in such a broad-based dialogue has really helped us navigate some of the challenges of caring for these people,” he said.