New medications for treating genetic metabolic bone diseases are driving results of a magnitude seldom seen in pediatric drug trials. For victims of three rare disorders – osteogenesis imperfecta, hypophosphatasia, and X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) – the impact ranges from more tolerable treatment regimens that lower fracture rates to a dramatic change in disease outcomes.

Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt is one of few centers to specialize in the treatment of children with rare metabolic bone diseases and is a top research site in the field. One of the most dramatic developments has been driven by burosumab treatment for XLH. Jill Simmons, M.D., a pediatric endocrinologist and director of the Program for Pediatric Metabolic Bone Disorders at Children’s Hospital, was a key member of the study team for the new medication.

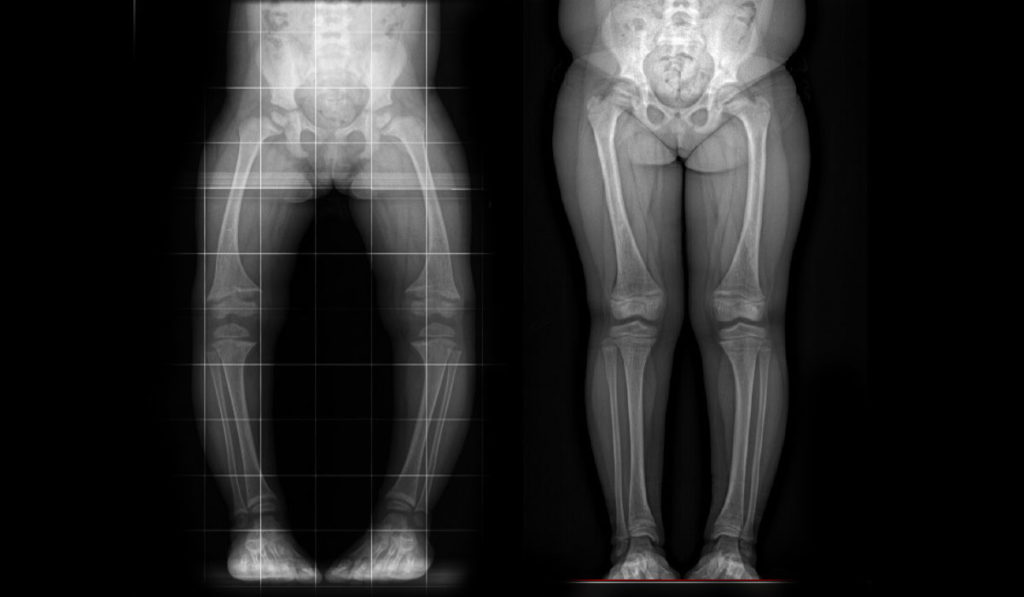

The phase 3 multisite trial on burosumab provided clear evidence that it vastly improves rickets, lower extremity bowing, linear growth, pain and physical function for the majority of patients. Newly published patient-reported outcomes of the trial support these findings, showing overall improvements in pain interference, physical function mobility and fatigue scores in these children.

“While it is not surprising to find that greater bone mineralization leads to decreased pain and improved physical function, it was important to measure this and to determine which patients experience these benefits,” Simmons said.

Attacking Bone Mineralization Deficiency

Many metabolic bone disorders result from (usually hereditary) genetic mutations that limit skeletal bone mineralization. In XLH, the body oversecretes fibroblast growth factor (FGF-23), which turns the kidneys into a sieve for phosphorus, decreasing bone mineralization. The resulting osteomalacia manifests in skeletal deformities like rickets, bowing and short stature in children. Adults with XLH have poorly healing fractures, chronic pain, and often limited mobility.

Until recently, XLH treatment consisted of four to six daily oral boluses of phosphorus as well as one to two times daily calcitriol. This therapy surfeits the bloodstream with phosphorus to try to outrun depletion in the kidneys. But the side effects of nausea and diarrhea are significant and compliance often suffers, Simmons says. Even with good compliance, improvement is marginal.

In contrast to this compensatory strategy, burosumab, a human monoclonal antibody, works by targeting the root of the problem FGF-23. With reduced volumes of this protein in circulation, the kidneys are able to naturally reabsorb more phosphorus.

The Burosumab Victory

The phase 3 burosumab trial included 61 patients, ages one to 12 years, enrolled across 16 sites and assigned to continued conventional or burosumab therapy. The primary endpoint was change in rickets severity at 40 weeks.

Radiographic evidence showed the 29 children receiving burosumab experienced double the improvement of conventional therapy in rickets and lower extremity bowing. Mild to moderate adverse events were more frequent with the treatment group but were generally consistent with subcutaneous injection.

“Now we have a disease-specific treatment for XLH that works for patients across their lifespan.”

Patient-reported outcomes were assessed for the children who were ≥ five years old at screening. Pain interference, physical function mobility, and fatigue scores improved from baseline with burosumab at weeks 40 and 64 weeks, but changed little with continued conventional therapy. Greater reduction in pain interference was noted in the burosumab group at week 40.

Patient and family perception of physical health scores (PHS-10) improved significantly with burosumab at week 40 and week 64, but not with conventional therapy. “This is significant improvement in just the first year or so. I expect to see a more dramatic improvement the longer patients are treated with burosumab,” Simmons said.

A Strengthening Trajectory

“Now we have a disease-specific treatment for XLH that works for patients across their lifespan, Simmons said. “We’ve seen it reverse rickets, decrease lower extremity bowing and even result in healing of previously non-healing fractures. Plus, these results are achieved through twice-monthly subcutaneous injections at home, versus requiring frequent oral medication that induces nausea and diarrhea.”

Trials on several promising new drugs to treat hypophosphosphatasia and osteogenesis imperfecta are also complete or in progress, Simmons said. She hopes these will enable these children to suffer fewer broken bones and spend less time sitting on the sidelines of life.