An easy-to-use bedside tool simplifies the diagnosis of spasticity, according to a study in Clinical Interventions in Aging done by Vanderbilt University Medical Center researchers including Mallory Hacker, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neurology and physical medicine and rehabilitation.

Until now, there have been no specific screening or diagnostic tools for spasticity, a problem affecting up to 35 percent of residents in long-term care facilities that often goes unrecognized or untreated. Scales that are currently used were designed to gauge the severity of spasticity, not for initial identification.

“The scales we have had available have all been administered by specialists, such as movement disorder neurologists or physiatrists, so they have really only been helpful after someone had already received a spasticity diagnosis,” Hacker said.

“The scales we have had available have all been administered by specialists … so they have really only been helpful after someone had already received a spasticity diagnosis.”

Identifying Overlooked Cases

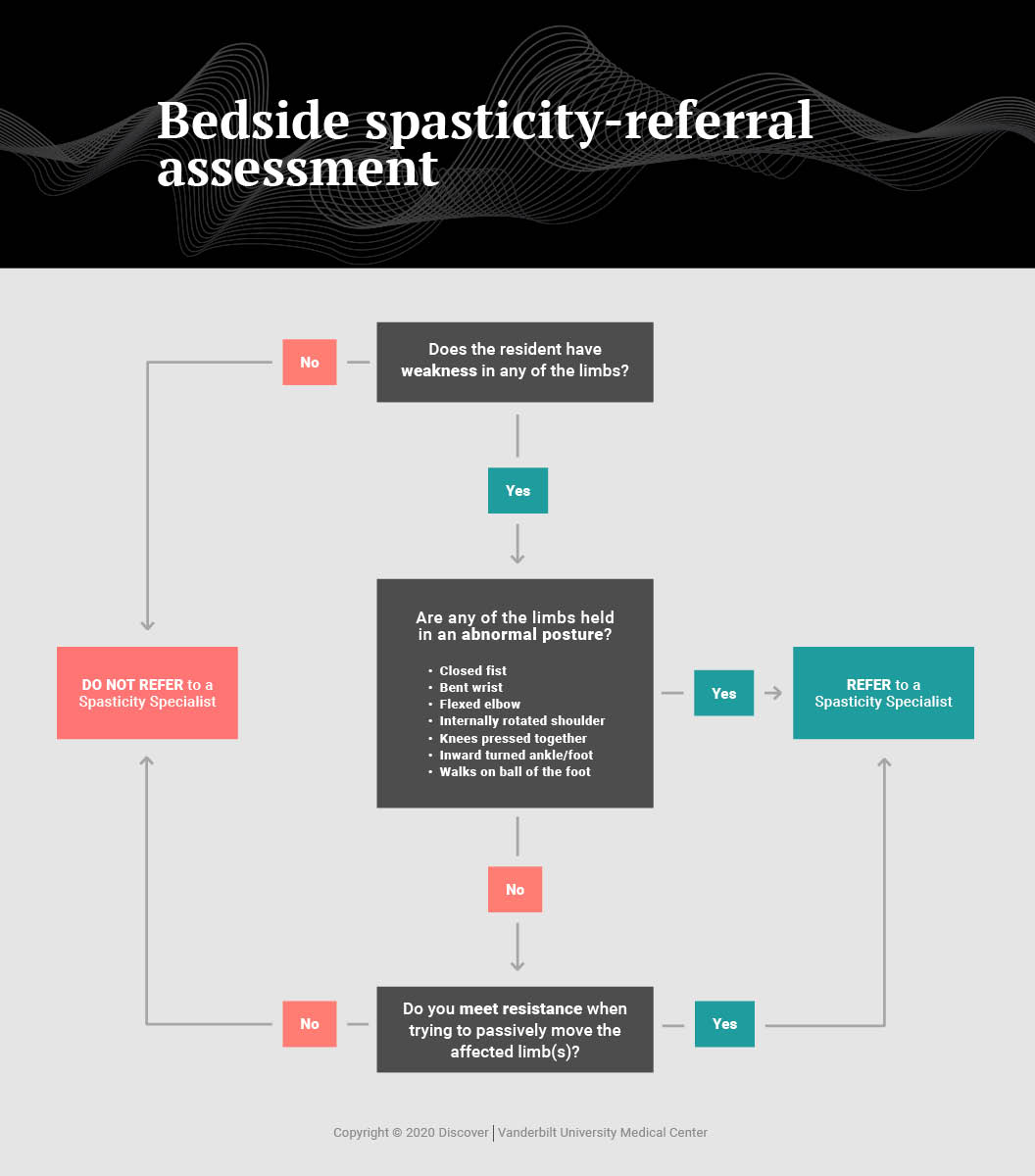

The new bedside referral assessment tool fills the critical gap in the spasticity diagnostic paradigm. “It’s designed to serve as a three-minute screening assessment for use by primary care providers who are unlikely to have specialty training in spasticity,” Hacker said.

Hacker originally developed and began testing the tool, a simple one-page flowchart, with David Charles, M.D., professor and vice-chair of the Department of Neurology at Vanderbilt. The tool asks three “yes or no” questions about resistance or weakness in the limbs and about any postural abnormalities that can serve as signs of spasticity. The answers can guide a decision about whether the patient needs to be further evaluated by a specialist.

“There are good, effective therapies available that can reduce the problems often associated with spasticity, but patients often receive no treatment for the condition because primary care providers working at long-term care facilities lack the time and the training to identify the condition,” Hacker said.

The researchers note untreated spasticity can cause pain, functional losses, and deformity, and degrade quality of life.

“There are good, effective therapies available that can reduce the problems often associated with spasticity, but … primary care providers working at long-term care facilities lack the time and the training to identify the condition.”

Study Shows High Sensitivity

In their most recent study, the researchers asked all the residents of a single long-term care facility or the people charged with medical decision making for them, to participate in the study. The analysis included 49 residents (80 percent male, average age 78 years), all of whom were evaluated by both a specialist trained to diagnose spasticity (a neurologist) and by at least one primary care provider, either a physician or a nurse practitioner.

The bedside referral tool demonstrated high sensitivity and moderate specificity when used by both the physician (92 percent and 78 percent, respectively), and by the nurse practitioner (80 percent and 53 percent, respectively).

Incidence of Spasticity Is Likely to Rise

In earlier research, Hacker, Charles and colleagues conducted what they believed to be the first study of the overall prevalence of spasticity among residents in a single nursing home. Although they identified 45 cases of spasticity out of 209 residents in that sample, only five diagnoses had been documented, a woeful degree of underdiagnosis.

Further, Hacker says the level of unmet need for spasticity treatment may trend upward as increasing numbers of patients are surviving after strokes, traumatic brain injuries, and spinal cord injuries, all of which can lead to spasticity.

The researchers encourage further investigation of the tool’s potential utility across multiple long-term care facilities and with various types of care providers.