Researchers may have found a way to circumvent diabetes that often follows stem cell and solid organ transplantation. Approximately one-third to one-half of transplantation recipients develop post-transplant diabetes mellitus (PTDM) as a consequence of drug regimens designed to prevent rejection.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight, researchers found a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist called exendin-4 successfully prevented beta-cell dysfunction caused by two common immunosuppressive drugs: the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus and the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus.

“Transplant patients are typically on life-long immunosuppression, and some develop PTDM years after transplant. Our results provide strong rationale for treatment with a GLP-1 agonist,” said senior author Alvin C. Powers, M.D., Joe C. Davis Professor of Biomedical Science at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and director of the Vanderbilt Diabetes Center.

Modeling PTDM

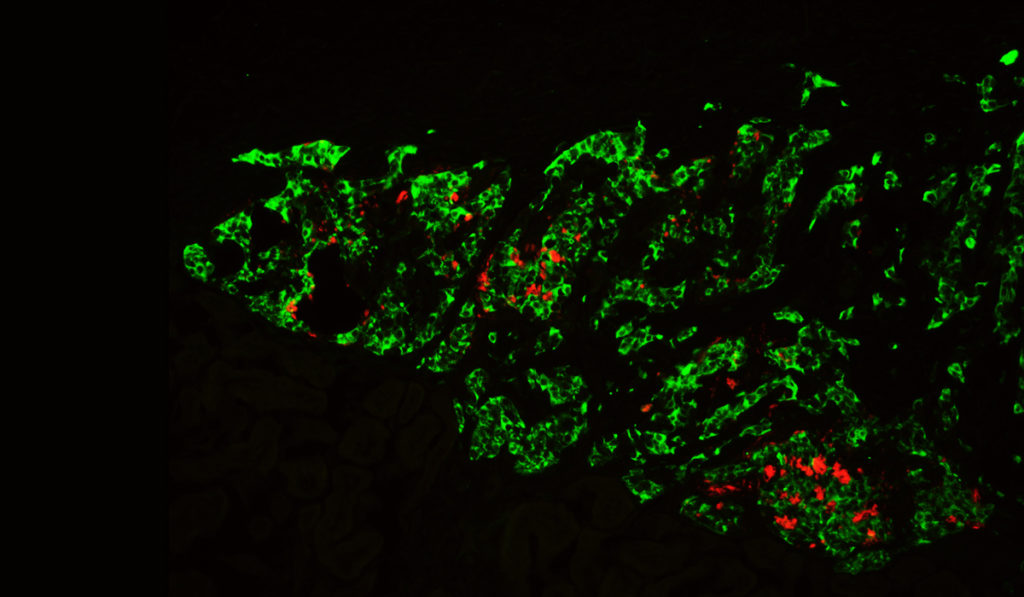

The researchers created a new model system to understand the long-term effects of immunosuppressive drugs on human islets. They transplanted human pancreatic islets into immunodeficient mice, then treated the mice with clinically relevant doses of either tacrolimus or sirolimus and monitored the mice for four weeks.

The human islets in mice treated with either drug secreted less insulin, a feature of PTDM. The transplanted human islets in treated mice also had reduced beta-cell granules, elevated proinsulin and increased amyloid deposits in the grafts — changes likely related to dysfunctional beta cells. Additional RNA analyses revealed “broad dysregulation of peptide processing, ion and calcium flux, and extracellular matrix maintenance,” wrote the authors. The findings point to key mechanisms connecting immunosuppressive medications to PTDM through their effects on the pancreatic islet.

Benefits of GLP-1 receptor agonist

Importantly, the immunosuppressive drugs’ effects on beta cells were reversible: when the researchers withdrew drug treatment, the beta-cell function returned to normal.

“This was a helpful finding — knowing the human islets were not permanently damaged — but withdrawing these drugs from transplant patients is not a viable option,” Powers said. “We needed to find another way to protect human islets from drug-induced dysfunction.” Chunhua Dai, M.D., a research associate professor of Medicine, John Walker, a M.D./Ph.D. student in Vanderbilt’s Medical Scientist Training Program, and senior research specialist Greg Poffenberger, M.S. conducted the studies.

“Withdrawing these drugs from transplant patients is not a viable option.”

The researchers turned to exendin-4, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, that targets a similar pathway to tacrolimus and has been shown to enhance beta-cell function, proliferation, and survival. GLP-1 is a hormone secreted by the intestines following oral glucose intake.

Mice who received exendin-4 concomitantly during the immunosuppressive drug treatment had improved insulin secretion, plus the human islets developed fewer amyloid deposits. Mice in the tacrolimus treatment group benefited more than those on sirolimus, which could help steer future research into underlying signaling pathways.

Translating the findings

Increasingly, providers are using GLP-1 agonists to treat type 2 diabetes because they improve glucose control with minimal risk of hypoglycemia.

While more research is needed to fully explore GLP-1 receptor agonists’ clinical utility in the context of PTDM, Powers believes the study with human islets could serve as a springboard.

“We hope these findings can be translated into clinical research, as these results suggest ways that diabetes associated with immunosuppressive drugs can be prevented or treated more effectively,” Powers said, adding that the new study is one of several ongoing at Vanderbilt to elucidate connections between stem cell transplant and diabetes.