By creating a series of new organoid models, researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center have established a unique approach to studying gastric cancer. The models allow researchers to track cell dynamics and identify key turning points in cancer development.

In results published in Nature Communications, researchers used the organoids to identify a new population of stem cells that arise during dysplasia. “We think this is the critical transition point between pre-cancer and cancer,” said senior author Eunyoung Choi, Ph.D., assistant professor of surgery at Vanderbilt.

“We think this is the critical transition point between pre-cancer and cancer.”

Gastric Cancer Organoids

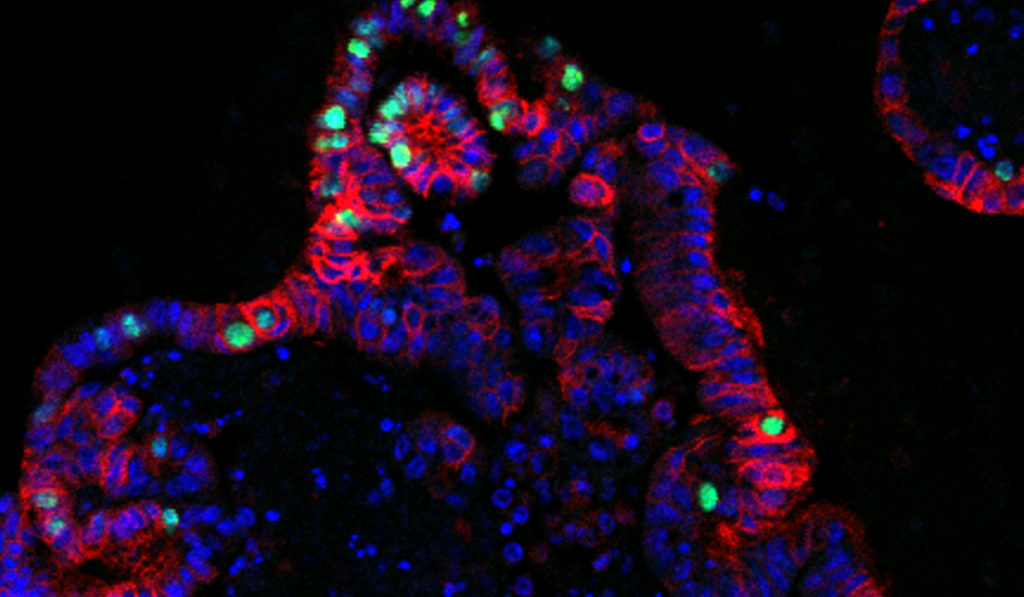

Organoids are increasingly popular research tools due to their ability to recapitulate complex tissues. They offer an in vitro system where multiple cell types can grow together in 3D. Gastric cancer organoids in the new study, for example, had multiple epithelial cell layers that regularly “budded” to form disorganized, complex structures.

“Metaplastic organoids are much better than just working with a cancer cell line,” said James Goldenring, M.D., Paul W. Sanger Professor of Experimental Surgery at Vanderbilt. “These ‘mini-stomachs’ can recapitulate many of the characteristics of the real lesions in the animal or human.”

Goldenring and Choi pioneered the first gastric cancer organoids. In the new study, the team established two specific kinds of precancerous organoids, derived from mouse stomach tissues. The models represent two early stages of gastric carcinogenesis: metaplasia and dysplasia.

Validated Models

The researchers monitored both organoid models as they grew. They tracked gene regulation, growth and other phenotypic changes. They even implanted the organoids into mice to confirm which properly mimicked gastric cancer.

The new organoids “display distinguishable structures and dynamic behaviors, pathological phenotypes and molecular signatures,” wrote the authors. “They have been continually passaged, undergone freezing and thawing following derivation, and maintained distinguishable structures as metaplastic or dysplastic organoids in 3D cultures.”

The durable models represent a new tool for testing drugs targeting early-stage gastric cancer in vitro – and for understanding gastric cancer development across its earliest stages.

A New Cell Population

Choi and colleagues compared the metaplastic and dysplastic organoids, looking for distinctions that might indicate cellular turning points.

Previously, Choi and colleagues showed selumetinib (a MEK inhibitor that blocks Kras signaling) can reverse gastric metaplasia. In the new study, selumetinib treatment slowed cell growth in both organoid models. The findings suggest Kras signaling might be “one of the dominant signaling cascades driving gastric carcinogenesis,” Choi said.

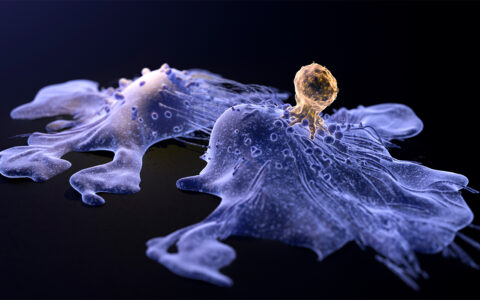

The researchers noted that some dysplastic organoids survived drug treatment. The persisting organoids displayed significant cellular heterogeneity and structures similar to the apical brush border. A closer look revealed the source: two dysplastic stem cell populations with vast clonogenic potential. Said Choi, “These surviving stem cells appear to be responsible, in part, for maintaining the organoids.”

Future Work

Until now, it has been difficult to identify which cells are involved in the steps leading to gastric cancer neoplasia. “Understanding dysplasia has been hampered by a lack of cell lines and accurate mouse models,” Choi said. “These new organoids show earlier phenotypes consistent with what we see in humans.” The newly identified stem cells also provide an opportunity to study molecular mechanisms behind the most aggressive, persistent gastric cancers.

The researchers plan to use their new models to further study the “gastric carcinogenesis cascade.” They are also hoping to launch a clinical trial this year of a MEK inhibitor designed to reverse metaplasia in gastric cancer patients.