Kidney stones are painful, but they are not commonly associated with serious, long-term side effects. Now, new research in Urology suggests stones may be associated with worsened cardiac outcomes after certain catheter-based interventions.

“Most people see kidney stones as an episodic condition… we uncovered more clinically consequential outcomes.”

“Most people see kidney stones as an episodic condition that rarely leads to kidney disease. It isn’t considered something with dangerous outcomes people would be concerned about,” said Ryan S. Hsi, M.D., assistant professor of urology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “In this study, we uncovered more clinically consequential outcomes.”

A Global Partnership

Together with Yu Shyr, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Biostatistics at Vanderbilt, Hsi measured cardiac outcomes across 167,051 adult patients – with or without stone disease – who underwent first-time percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs).

The researchers dug into EHRs from both the United States and Taiwan to help ensure results were generalizable. Biostatisticians at Vanderbilt and National Cheng Kung University helped mine retrospective data related to stone history, myocardial infarction and in-hospital mortality. First author Chao-Han Lai, M.D., who holds appointments at both institutions, spearheaded the effort and connected the research teams. The study was the first to analyze kidney stone disease using Vanderbilt’s Synthetic Derivative.

Increased Odds

Across matched Vanderbilt and Taiwanese populations, kidney stone history was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction at one and three years post-PCI. In the Vanderbilt population, having a history of kidney stones also was associated with an increased risk of 30 day in-hospital mortality.

The study provides outcome data for a growing body of research, Hsi said. “Evidence that links stone disease with cardiovascular disease is being seen in all populations, not just Western populations.”

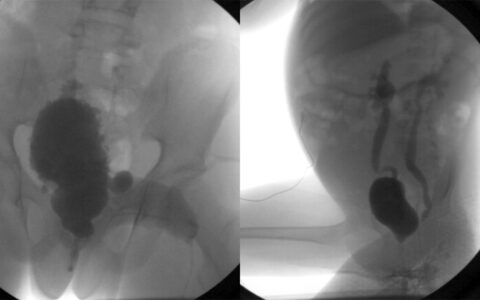

The findings further connect coronary artery disease and kidney stone disease – a link Hsi says he is often reminded of during surgeries. “In our surgeries, when we look up into the kidneys and see the papilla from the inside, we have a tiny view of the vascular health of the patient. Often times you’ll see plaques and stones attached to the vasculature, and it makes you wonder, is there something going on at the heart level?”

Patient Counseling

Hsi already counsels patients with kidney stones on lifestyle and diet to reduce their risk of developing coronary artery disease, but does not advocate for treating them with statins or other cardiac medications based on the study results. “It’s reasonable to inform patients with stones of their cardiovascular risk, but how we intervene is an area that needs further research.”

“It’s reasonable to inform patients with stones of their cardiovascular risk, but how we intervene is an area that needs further research.”

However, physicians may need to manage patients undergoing PCI a little differently in the clinic, Hsi says. Those with kidney stone history may require more aggressive follow-up or secondary cardiac prevention measures.

To understand how additional interventions might help, Hsi is continuing to analyze EHR data. “We’re developing tools to structure the EHR so we can ask more specific questions about this patient population. We’re also building tools to link EHR to imaging and genetic data, with the ultimate goal of better phenotyping kidney stone patients.”