Researchers have long associated kidney injury and DNA damage. Kinases that sense DNA damage, such as ATR, can help renal cells overcome injury. However, this DNA damage response is so ubiquitous in the body, it’s difficult to study.

“You can’t knock out ATR in a whole animal, because they develop progeria, or accelerated aging,” said Craig Brooks, Ph.D., nephrology researcher at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “We designed an approach to knock it out immediately before inducing kidney injury,”

In The Journal of Clinical Investigation, Brooks and colleagues, including Joseph Bonventre, M.D., and Seiji Kishi, M.D., of Harvard Medical School, applied the technique to show ATR regulates beneficial DNA repair in proximal tubule cells. They found the kinase can aid in preventing maladaptive renal injury responses, in doing so helping to settle a longstanding debate over the importance of repairing damaged cells following acute kidney injury.

A Focused Approach

“Proximal tubule epithelial cells are the most sensitive cells to injury in the kidney,” Brooks said. “We specifically deleted ATR in these cells, and tested their ability to recover from three types of kidney injury.”

The researchers studied the effects in tubular injury caused by either bilateral ischemia-reperfusion, cisplatin (a chemotherapeutic), or unilateral ureteral obstruction. All three are common causes of kidney injury in hospitalized patients, and have distinct pathologies.

Said Brooks, “We wanted to know, if we remove a major DNA damage sensor, what does that do to kidney disease?”

DNA Damage Increases

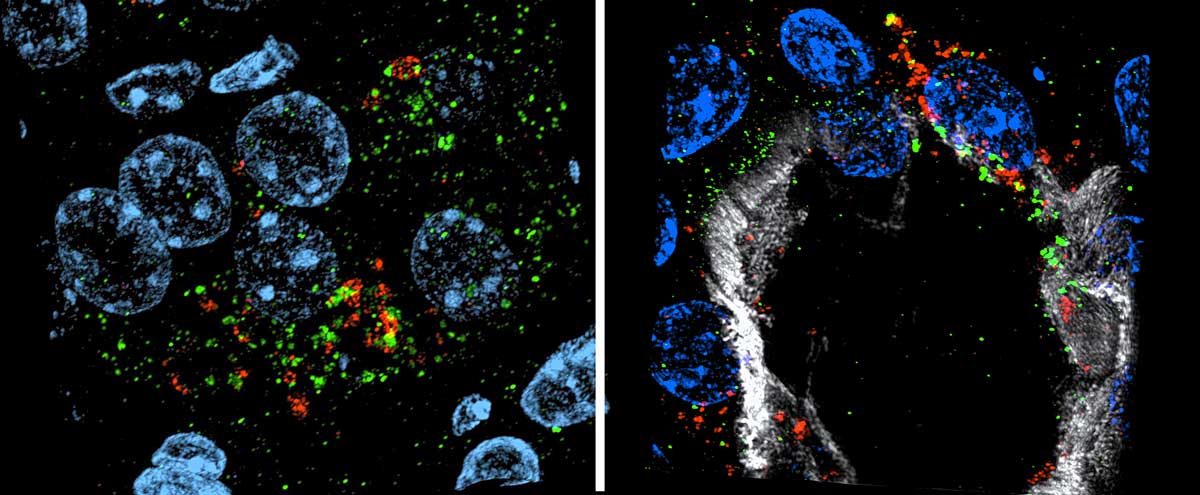

First, the researchers showed ATR is activated and DNA damage is high in tissue biopsies collected from patients with chronic fibrotic kidney disease, and in kidney organoids derived from human stem cells. Then, after deleting ATR and inducing injury, they showed DNA damage increased in the models.

“In every model we tested, the kidney injury was substantially worse, especially in the repair phase.” Brooks said. The cells arrested in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. They became senescent and began secreting profibrotic factors before dying off. Since the kidney normally has a high reparative capacity, the findings suggest ATR may underlie this important ability.

Monitoring Combination Therapy

One of the models in the study used cisplatin, a common chemotherapeutic, to induce kidney injury in mice. “One of cisplatin’s limiting factors is it causes kidney toxicity,” Brooks said. “The kidney has specific protein transporters that uptake cisplatin into cells, so the drug’s concentration in sensitive proximal tubule cells is much higher than in other tissues.”

Currently, there are ongoing clinical trials testing ATR inhibitors – many of which are to be used in combination with cisplatin to shrink tumors. Said Brooks, “Combination therapies are very effective at shrinking tumors; however, we need more data to determine if there is potential for increased kidney toxicity with these therapies.”

Brooks suggests increased monitoring for kidney injury for ATR inhibitors, particularly when used in combination with other drugs known to cause kidney toxicity.