Myocarditis is a leading cause of heart failure in children and young adults. Its clinical picture is variable from asymptomatic to fulminant. Symptomatic cases usually present in an acute state and are typically diagnosed in an emergency setting. In most cases, health care providers can only support the patient through the acute phase and then prescribe medications to help compensate if there is permanent heart damage.

In hopes of changing this grim scenario, a research team led by Daniela Cihakova, M.D., of Johns Hopkins University, with the collaboration of Vanderbilt University Medical Center fellow Giovanni Davogustto, M.D., (formerly a member of Heinrich Taegtmeyer, M.D.,’s lab from McGovern Medical School), are working to understand the inflammatory cascade that propels the disease. Their most recent study, published in Cell Reports, describes a chain of events mediated by interleukin-17A (IL-17A), a proinflammatory cytokine, which leads to development of a “bad” type macrophages that promote excessive inflammation and fibrosis.

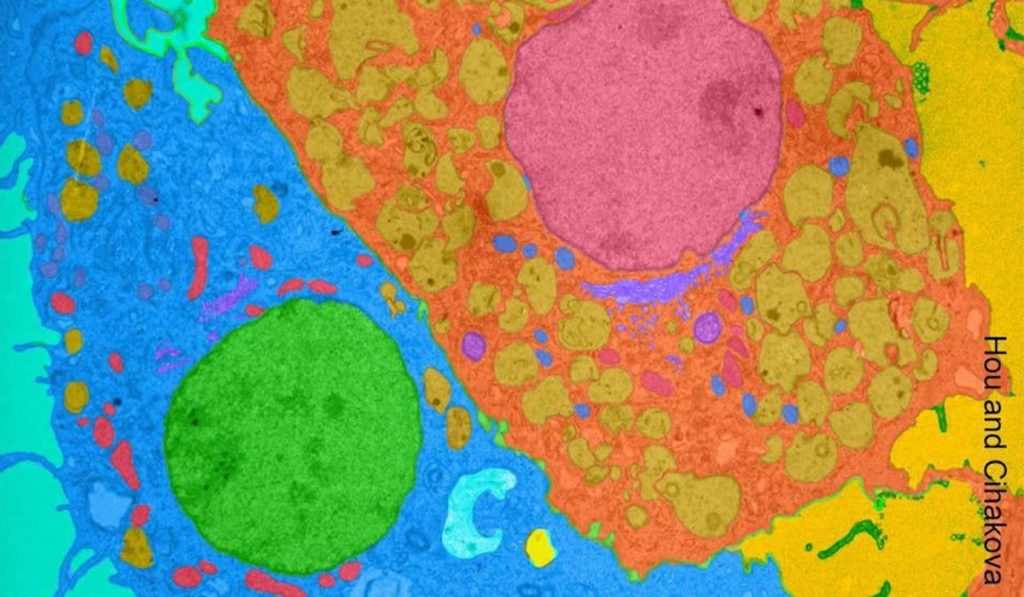

First author of the study, Xuezhou Hou, Ph.D., describes downstream mechanisms of IL-17A and quantifies its impact through in vitro, mouse models and human heart tissue samples obtained from patients undergoing left ventricular assist device implantation at the Texas Heart Institute. “The goal is to understand the mechanisms of myocarditis, and eventually explore the development of therapeutic interventions to help our patients,” Davogustto said.

Determinants of Healthy Response

Macrophages, part of the body’s “clean-up crew,” play a key role in determining outcome in myocarditis. In the heart, there are two types of macrophages. Ly6Clo (low) macrophages tend to play a scavenger and reparative role, selectively surrounding and eliminating cellular debris. Ly6Chi (high) macrophages are less discriminating and tend to play a more inflammatory role, with implications in loss of normal tissue structure.

“Think of Ly6Clo as the disciplined one, eating moderately and cleaning its plate. Ly6Chi is the out-of-control sibling who starts eating and doesn’t finish, going on to the next plate and leaving a mess behind.” This “mess” contributes to inflammation and tissue damage.

“Ly6Chi is the out-of-control sibling who starts eating and doesn’t finish, going on to the next plate and leaving a mess behind.”

In the inflammatory response of myocarditis, IL-17A stimulates fibroblasts to secrete GM-CSF, a cellular growth factor which play cytokine-like functions. GM-CSF, in turn, regulates the differentiation of monocytes into each type of macrophage. It is when the Ly6Chi macrophages are produced disproportionately to the Ly6Clo that inflammation can spiral out of control, leading to long-term damage.

Study Findings

The researchers found that in the absence of IL-17A, fibroblasts do not secrete GM-CSF, and monocytes do not convert to the Ly6Chi type of “bad” macrophages, while development of Ly6Clo macrophages continues. When GM-CSF is excessive, a higher quantity of Ly6Chi versus Ly6Clo macrophages are produced.

“I believe it’s a balance issue – you will always have the high and low types, but the ratio determines how the disease will go, and that is determined by how much IL-17A is in the mix,” Davogustto said.

Cihakova’s group found that one reason Ly6Chi macrophages are more harmful in the progression of myocarditis is that IL-17A causes shedding of a type of scavenger molecules on their surfaces, making them less effective at their mine-sweeping jobs.

Challenges to Therapies

Because IL-17A is one of the mediators of the immune response in myocarditis and critical in the progression toward heart failure, it is implicated in the development of cardiac fibrosis and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), the feared sequelae of myocarditis. The study findings point to IL-17A and GM-CSF as therapeutic targets for avoiding this cascade toward DCM development, by managing the relative levels of differentiation from monocytes to “bad” Ly6Chi macrophages versus “good” Ly6Clo macrophages.

“However,” Davogustto said, “One of the big challenges will be to identify the appropriate time frame for a therapeutic intervention.”