Increasingly, addiction is understood as an enduring brain disease that long outlasts acute physiological withdrawal. Negative affective symptoms such as anxiety, depression and stress associated with prolonged alcohol abstinence are now thought to be leading causes of relapse. To develop interventional strategies, understanding neural mechanisms that drive drug “craving” and relapse is crucial.

“We’re learning how alcohol withdrawal impacts the brain,” said Danny Winder, Ph.D., director of the Vanderbilt Center for Addiction Research (VCAR). “We now think that negative affective disorders that occur after a period of forced abstinence are triggered in part within the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), the tiny region of the brain adjacent to the amygdala. By identifying how the circuit works we can begin to test pharmaceutical interventions.”

Testing Agents to Lessen Withdrawal

Winder’s lab has developed a mouse model of chronic drinking/forced abstinence to study the neurologic effects of alcohol withdrawal. In their first study using the model, the investigators found that depression-like behavior occurred only after a protracted (two weeks), but not acute (24 hours), abstinence period. Once established, the affective disturbance was long-lasting, but could be reversed utilizing the N-methyl D-aspartate receptor antagonist and antidepressant ketamine.

A second study assessed whether ketamine can be used to prevent development of abstinence-dependent affective disturbances. While administration of ketamine in early abstinence was associated with disrupted negative affect, ketamine administered two to six days post-abstinence failed to prevent the affective disturbances.

“There’s a lot of excitement and a lot of controversy around ketamine,” Winder said. “We’re using compounds that share properties of alcohol as preclinical tools to tap into mechanisms that can lessen this affective state; to find more selective targets. My fear is that we will make an abstinent alcoholic feel better, but you might also give them an alcohol reminder trigger of what it feels like to be intoxicated.”

Winder’s most recent study, in collaboration with Sachin Patel, M.D., director of the Division of Addiction Psychiatry at Vanderbilt, was published last fall. It explored the potential around pharmacological enhancement of endogenous cannabinoid (eCB) signaling in abstinence-associated negative affect. The investigators found that eCB prevented abstinence-induced increases in BNST neuronal activity, underscoring the therapeutic potential of drugs targeting the brain’s eCB system.

Mapping the BNST with Advanced Imaging

“How would we image the BNST, which is the size of a sunflower seed?”

Winder collaborates closely with Jennifer Blackford, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and psychology at Vanderbilt. Blackford’s research focuses on anxiety vulnerability and anxiety disorders. Intrigued by the preclinical findings supporting the importance of the BNST for anxiety, Blackford wanted to examine BNST function in humans, but asked: “How would we image the BNST, which is the size of a sunflower seed?”

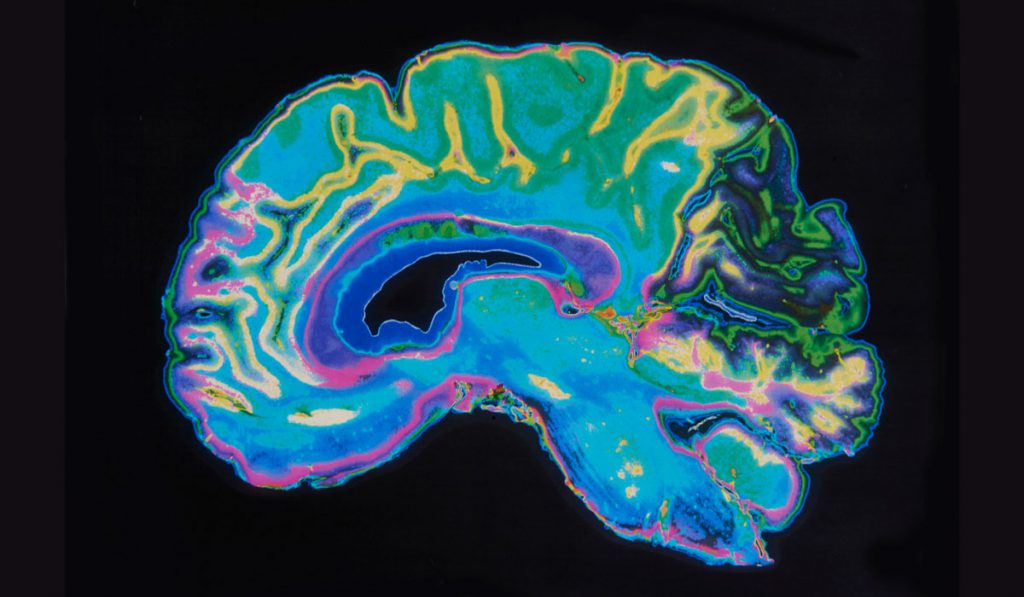

To construct her map, Blackford turned to Vanderbilt’s vast imaging resources, which include a 7-Tesla MRI. Blackford was able to reliably identify the human BNST and published a study demonstrating that the human BNST shares the same functional and structural connections observed in monkeys and rodents. Blackford and Winder were excited about the translational findings and have received a National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant to study BNST function and connectivity during early abstinence from alcohol in humans.

A Meaningful Role for Research Participants

To recruit participants for brain imaging, Winder and Blackford have partnered with Cumberland Heights, an established drug and alcohol treatment center in Nashville. Participants must have one to six months of abstinence from alcohol with anxiety and depression symptoms. “Preliminary data have been very compelling,” Blackford said.

Blackford will identify behavioral therapies that impact the BNST. Winder is using the map to test pharmaceutical interventions. By studying the human BNST during early sobriety, Winder and Blackford hope to translate their work to the clinic.

“The VCAR allows those of us who do basic science to better interact with clinicians and clinical scientists,” said Winder. “If we can find interventions that keep people from relapsing, we will have a positive impact on the disease of addiction.”