Frailty is most often defined as a generalized risk state of physiologic decline, marked by increased vulnerability to injury, disability and death. Frailty is a strong predictor of poor health outcomes in normal aging.

New research suggests patients entering the intensive care unit (ICU) with preexisting frailty have worse outcomes post-hospitalization than those without the syndrome. A stay in the ICU also appears to increase the risk of frailty and associated health problems following hospitalization. Until recently, few studies had explored the connection between frailty and ICU survivorship.

“As evidence is mounting that a significant number of ICU survivors experience cognitive problems, disability and increased mortality risk, establishing a better understanding of frailty may help explain why those problems develop,” said Nathan Brummel, M.D., an assistant professor in the Division of Allergy, Pulmonary and Critical Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Brummel is helping lead a series of multisite studies exploring frailty in the context of the ICU.

Frailty Entering Critical Illness

“Our first approach, which we reported in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine in 2017, was to ask whether or not patients’ state of frailty before they came into the ICU had a significant impact on outcomes after they were discharged,” Brummel said.

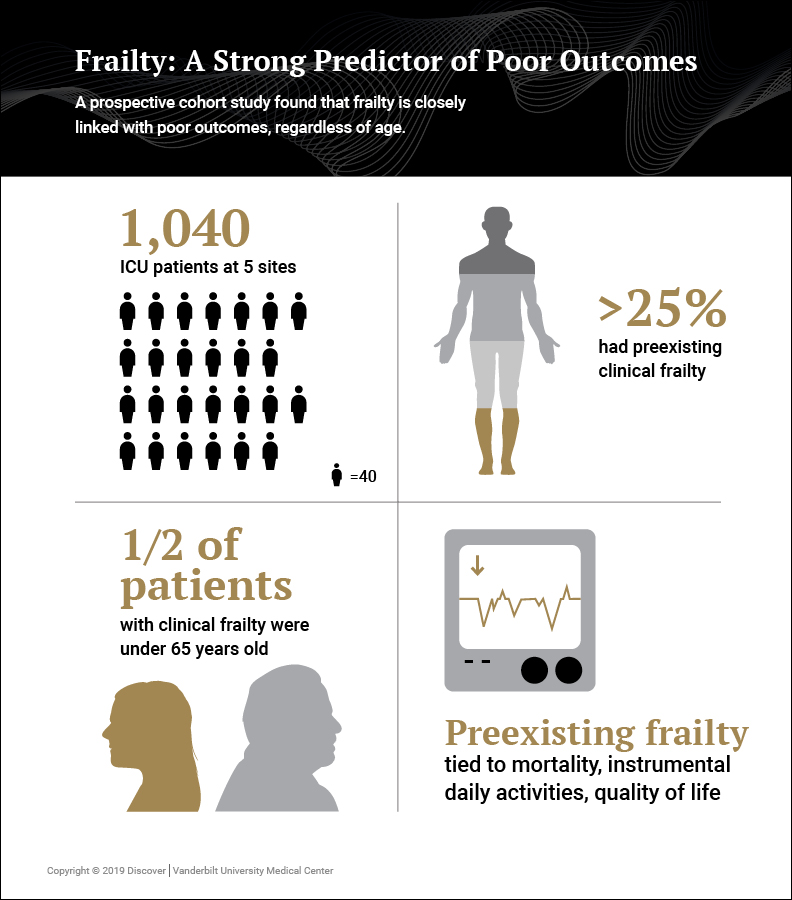

The prospective cohort study tracked 1,040 patients across five centers who were admitted to the ICU for respiratory failure or shock. Patient or proxy interviews and medical records were used to determine whether a patient had preexisting frailty, as measured by the Clinical Frailty Scale, which classifies patients along a continuum from “very fit” to “severely frail.”

Researchers tracked patients through their stay in the ICU and followed up at 3 months and 12 months post-discharge. After accounting for potential confounding factors (e.g. baseline cognitive function, ICU illness severity), they found preexisting clinical frailty was independently associated with greater mortality, greater odds of disability in activities of daily living and poorer physical health-related quality of life.

“Among other significant findings, the study shows a simple scale at ICU admission can identify patients at increased risk of poor outcomes,” Brummel said.

Rethinking Frailty and Age

“Frailty was predictive of poor outcomes… regardless of whether the patient was 25 or 85.”

Although frailty is traditionally viewed as a geriatric syndrome, 50 percent of study participants with clinical frailty were younger than 65. Approximately 20 percent of those patients entering the ICU with clinical frailty were under age 50.

“Our results suggest that preexisting frailty, as measured by the Clinical Frailty Scale, is common in critically ill patients regardless of age,” Brummel said. “Frailty was predictive of poor outcomes such as disability and death regardless of whether the patient was 25 or 85.”

Brummel is interested in studying an alternative model of frailty focused on physical criteria such as muscle weakness, slow walking speed, weight loss and low energy. Better understanding frailty as a physiological state may lead to more effective interventions for ICU survivors across age groups.

“Age, or chronological age, is a bad predictor of outcomes,” Brummel said. “When we start to dig a little deeper, it may help us understand these patients better.”

New Frailty Studies

As a follow-up, Brummel’s research group is studying those patients who entered the ICU without documented frailty, but who developed it during their stay or recovery. “Only about 25 percent of patients had frailty when they came into the ICU, but 40 percent had frailty at 3 months and 12 months afterward. Something related to their critical illness and their hospitalization seems to be leading to that increase in frailty,” Brummel said.

Additionally, the group is planning a longer follow-up study of patients for up to 3 years after their ICU stay. “We still have many questions about frailty and outcomes after critical illness. Frailty can be a very dynamic condition. We don’t have enough information yet about how frailty goes in these survivors — particularly younger patients,” Brummel said.

Brummel is also leading research to identify more effective screenings and therapies within the ICU that may reduce frailty and its severity during survivorship. “A natural extension of having data from these studies is developing a tool or some other measure to identify which patients are at risk of poor outcomes, and how to better devote resources within the ICU to help them,” Brummel said.