Jed Kuhn, M.D., Kenneth D. Schermerhorn Professor of Orthopaedics at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, is helping lead a new, multicenter study investigating outcomes for patients with atraumatic rotator cuff tears receiving operative versus non-operative therapy. Kuhn is co-investigator for the study alongside Nitin Jain, M.D., an associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and Orthopaedics at Vanderbilt. The research is supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

Discoveries: This new study is focused on the two main treatments for rotator cuff injuries: surgery and physical therapy. Can you say more about the research?

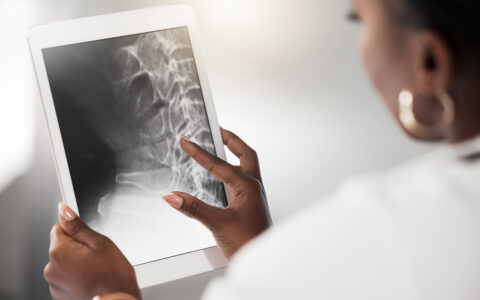

Kuhn: The patients that we’re researching have rotator cuff tears without having had a traumatic injury. They show up in the doctor’s office with shoulder pain, and an MRI scan shows a rotator cuff tear. There is debate about how to treat those patients best. Some patients would like to have surgery. Some patients would do better with non-operative treatment. We don’t have strong research supporting the right thing to do.

This study is a randomized trial. If patients decide to participate, we’ll open an envelope and randomize them into either non-operative treatment or surgery. At the end of one year, two years, five years, and ten years, we can assess how those patients are doing and determine the best treatment.

Discoveries: Have you researched this question through any previous studies?

Kuhn: I oversee a group of shoulder surgeon scientists across the country called the MOON (Multi-Center Orthopaedic Outcome Network) Shoulder Group. We decided to look at this question. We sent every patient with an atraumatic rotator cuff tear through a physical therapy program. Much to our surprise, over 80 percent of those patients got better and declined surgery. They felt great. Their pain went away. They were very happy with the non-operative treatment.

As surgeons, that surprised us. We thought about 15 percent of people would do well with therapy, not 80 to 85 percent. So, we looked back at our data to understand this better. Studies in our literature have shown that people who have rotator cuff tears based on MRI scans may be completely asymptomatic. Somewhere between 10 and 40 percent of people over the age of 60 have rotator cuff tears and don’t know it. What I think we’re doing with physical therapy is taking someone who’s symptomatic and making them asymptomatic with the exercise program. They still have the rotator cuff tear, but their pain is gone.

On the other hand, surgery can be helpful for patients. It can restore strength. Patients who’ve had surgery tend to do well. There is also some question whether or not surgery may prevent rotator cuff tears from enlarging over time and causing disability later in life.

Discoveries: Would you explain the structure of this study?

Kuhn: This is is a PCORI grant and was written by Nitin Jain, a physiatrist here at Vanderbilt with a strong interest in musculoskeletal medicine. I oversee the surgical aspects. Kristin Archer (Ph.D., associate professor of Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation and Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Vanderbilt) oversees the rehabilitation aspects. We have biostatisticians who oversee the statistical parts.

Patients are enrolled in about 15 centers around the country. Most are academic medical centers, but there are two private practice groups. We have a nice spectrum of patients and practice patterns to recruit from.

Discoveries: What’s the timeline for completing this research?

Kuhn: We’re just about to start enrolling patients. We anticipate enrolling for about two years to get 750 patients in total. We may be following these patients for 10 to 15 years to know the best long-term treatment.

Discoveries: Are there comparable studies in other areas of orthopedics?

Kuhn: These studies are very hard to do. It’s hard to have equipoise–you need a surgeon that believes therapy can work and knows that they don’t know the right answer. It can be a challenge finding surgeons willing to participate in a study that may demonstrate therapy can be a better treatment.

There was a study fairly recently looking at degenerative meniscus tears in the knee. They treated patients with therapy or with arthroscopic surgery. It was a randomized trial. Again, they found that surgery didn’t provide much benefit that therapy did not, particularly if the patient had arthritis in their knee. That type of study can change the way people practice and can be very impactful, but it’s hard to do.

Discoveries: What are you excited to learn from this research in terms of variables impacting patient outcomes?

Kuhn: In an earlier study of patients sent through physical therapy, where 80 percent got better with the therapy, we were surprised that the strongest predictor of surgery was the patient’s expectations. If a patient thought therapy would work, it would work. If a patient didn’t think therapy would work, they had surgery. The decision to have surgery had nothing to do with the anatomy of the rotator cuff, the size of tears, the level of pain, or patients’ levels of activity. That didn’t turn out to be true. What drove the decision to have surgery was the patient’s perception.

As orthopedists, our work is below the chin. It’s in the shoulder. It’s in the knees. We may not think about how patients are thinking. But clearly, how patients are thinking matters. As surgeons, we sometimes have to tell patients, “This is what the data shows. Believe it or not, even though you came here thinking you would need an operation, you probably will do very well with physical therapy.” So the management in the clinic can be very important.

Discoveries: Have you seen that same interplay between a patient’s attitude and treatment in other areas of orthopedic injury?

Kuhn: Kurt Spindler, who did the MOON ACL studies of anterior cruciate ligament tears, has looked into fear avoidance and the ability to return to sport. People may injure their knee playing a sport, have a successful surgery and still may not be able to return to the same level of sport. Patient expectations and fear strongly influence the ability to return to play. Again, it’s very important how patients are perceiving the world, and how you manage your patients and their expectations.

Discoveries: As a surgeon, how are you thinking about what you’re beginning to learn through these studies?

Kuhn: We’ve learned a lot so far. We’ve recognized that the relationship between pain and rotator cuff disease is not very robust. We looked at whether or not pain correlates with the size of the rotator cuff tear, and it’s not true. The size of the rotator cuff tear has nothing to do with the patient’s pain level.

“As surgeons when we look at an MRI scan and we see something abnormal, we can’t make an assumption that it’s responsible for the patient’s symptoms. Physical therapy gets many patients better, but they still have the same MRI scan when they’re done.”

We looked at the patient’s duration of symptoms. You might think that someone with symptoms for a longer period of time would have a larger rotator cuff tear. We found that was not true, either. We also looked at activity level and found it was not true that patients who were more active would have smaller tears, or that patients with larger tears were not as active.

So, as surgeons when we look at an MRI scan and we see something abnormal, we can’t make an assumption that it’s responsible for the patient’s symptoms. Physical therapy gets many patients better, but they still have the same MRI scan when they’re done. What’s also interesting is that when we repair rotator cuff tears and they fail, those patients may say, ” I feel great. I have no pain. I’m doing wonderfully.” What we were taught that the rotator cuff was the source of the patient’s problems may not be true, which is fascinating.

We do know that strength is important. If a patient’s symptom is related to weakness or functional loss, then the rotator cuff tear is probably responsible. Fixing that rotator cuff is really the only way to get strength back. When I look at patients, I try to get an idea about their primary concern. If it’s pain, I let them know that physical therapy can [manage their pain] very effectively. If their issue is more function or strength problems, then I usually talk to them about surgery. It’s hard to get that back through therapy. Strength gains are better if the rotator cuff repair heals.

Discoveries: Within the area of surgery, what new approaches are most exciting for treating rotator cuff injuries?

Kuhn: Rotator cuff disease is a phenomenon of aging. If you live long enough, you’ll eventually have a rotator cuff tear. It’s hard to use surgery to repair aging. So the things that are most exciting are the therapies that may improve healing and rejuvenate tissue: biological materials to improve the healing of rotator cuff tears, platelet rich plasma, stem cells. If we can find something that reverses the aging process in the rotator cuff, we’ll have higher healing rates.

Discoveries: How can patients who may be interested in the study get in contact?

Kuhn: The institutions that are involved include Vanderbilt University, the University of Kentucky, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Texas Southwest at Dallas, the University of California San Francisco, the University of Colorado, the University of Michigan, the Ohio State University, Washington University in St. Louis, the University of Iowa, and the Knoxville Orthopedic Clinic in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Discoveries: Thanks for talking with us today.

Kuhn: You’re welcome.