Diabetes is a multi-billion dollar industry in the United States, racking up $237 billion in direct medical care costs in 2017. An estimated 1 in 4 health care dollars is used to treat the 23 million Americans with diagnosed diabetes.

Many insulin formulations are available to help patients manage their diabetes. But between 2002 and 2013, the price of insulin nearly tripled. Individuals with diabetes can pay $1000 or more each year for insulin—plus the price of a pump and other diabetes supplies. Increasingly, many patients are rationing their insulin supply, or prioritizing other expenses, putting their health in jeopardy.

The reason for increasing prices is extremely complicated, said Alvin C. Powers, M.D., the Joe C. Davis Chair in Biologic Science and director of the Vanderbilt Diabetes Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “Everyone wants to blame one person, or entity, but that’s not a productive way to look at it. Several aspects of the health system are responsible.”

Assessing the Supply Chain

“We invited people across the insulin ‘ecosystem’ to talk with us about why prices are going up, and what can be done about it.”

In his role as President, Medicine and Science, of the American Diabetes Association, Powers recently participated in a 13-member Insulin Access and Affordability Working Group to investigate rising insulin costs. The group’s findings were published in Diabetes Care.

“We invited people across the insulin ‘ecosystem’ to talk with us about why prices are going up, and what can be done about it,” Powers said. “Everyone realized it’s an issue.”

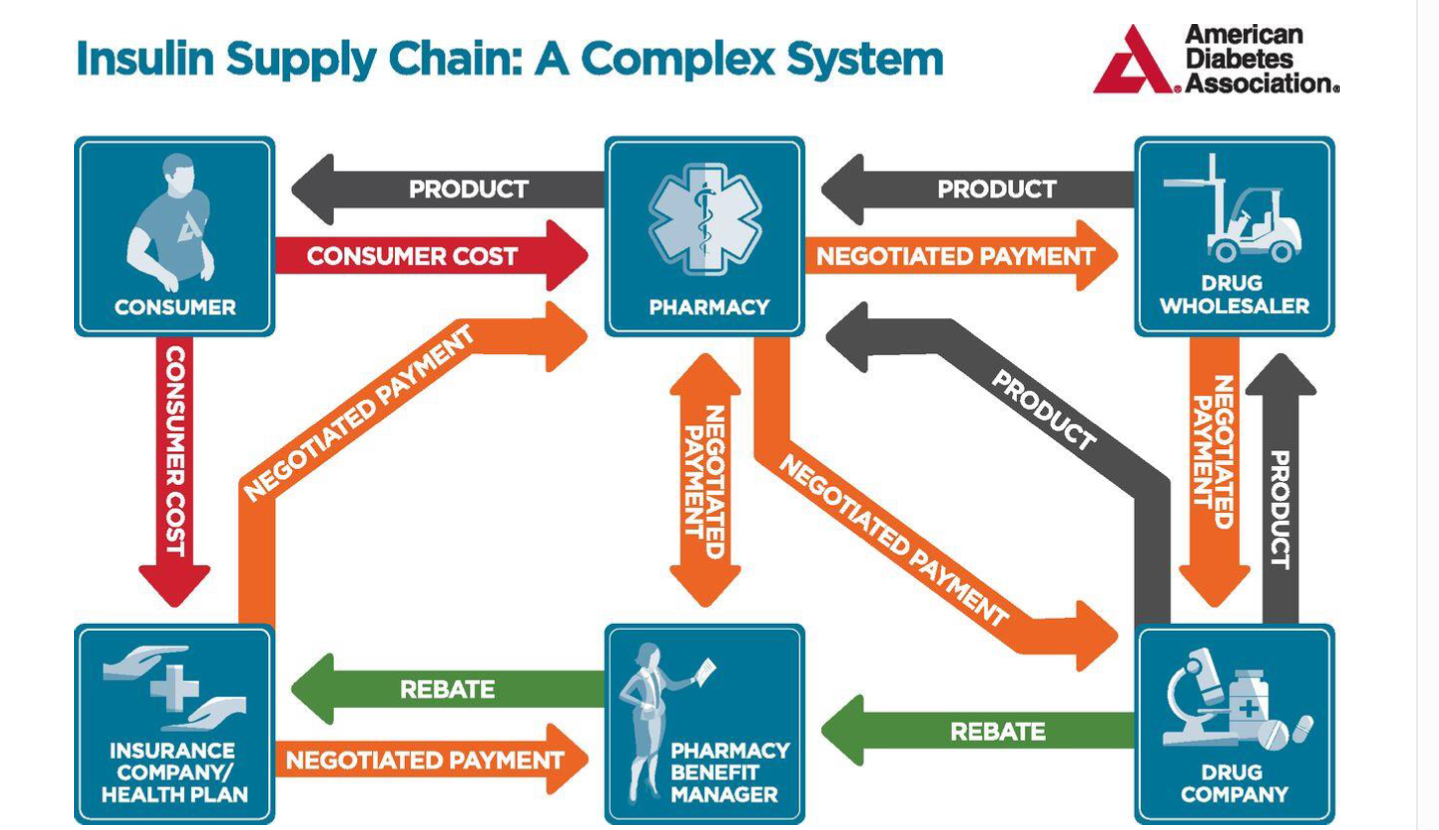

The group talked with more than 20 stakeholders in the supply chain, including manufacturers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), pharmacies, insurance providers, prescribers, and patients. They found rising costs at every level, with a growing gap between list and net prices across four insulin categories.

“While the medication itself takes a rather direct path from manufacturer to wholesaler to pharmacy to patient, the flow of money is far less direct and transparent,” wrote the authors.

The group found average out-of-pocket spending for all insulins rose to over $700 in 2013. This cost is the culmination of prices, rebates, and discounts set by supply chain stakeholders—who each have varying degrees of negotiating power, and varying interests in certain formulations.

Choosing the Right Insulin for the Right Patient

“Part of the confusion is how do you get the right insulin for the right patient. One size doesn’t fit all,” Powers said. Providers often choose an insulin from a formulary, that is set by PBMs.

Since 2000, providers have shifted to prescribing higher-priced insulins such as analogs that are increasingly common on formularies. Insulin analogs can cost three times as much as alternatives yet now account for 9 out of 10 insulin prescriptions. Said Powers, “I think it’s mostly driven by habit and marketing. Physicians are encouraged in a variety of ways to prescribe the newer insulins, which are much more expensive.”

PBMs are not entirely to blame, cautions Powers. They act as intermediaries that must balance insulin manufacturing company and insurance plan priorities. Yet PBMs earn rebates—and leverage—for this intermediary role. They also have tremendous influence on a drug’s market value. Nationally, PBMs manage approximately 70% of all prescription claims. They are highly valued—Cigna recently paid $67 billion to acquire a single PBM.

Strategies to Lower Costs

“At Vanderbilt, we have our own PBM that doesn’t offer rebates. It’s not one we own, it’s a private company, but it operates in a very different way,” Powers said. Vanderbilt serves as a self-insured payer for health care, giving the institution more leverage in negotiations.

“There may be two insulins that are clinically identical, but Vanderbilt can negotiate a better price for one than the other,” Powers explained.

In-house negotiations can also help avoid cost increases due to shadow pricing, whereby as the price of one insulin goes up, the price of competing products also go up. The common practice is found in many industries (airlines, for example), but can contribute to health disparities when it comes to medication pricing.

“We’re working to make sure patients get the right insulin, and that physicians are given guidance on which insulin to order,” Powers said, also noting efforts by Vanderbilt’s Department of Health Policy to increase medication access. “We’re defining our formulary in conjunction with our health care providers. We’re not just trying to limit cost. We’re trying to get the best insulin at the best price.”